There have been many bad days in the two months since the war began, but none have seen Russia’s cynicism more openly. Five civilians, including a three-month-old baby, his mother and grandmother, were killed in the Russian missile attack on Odessa on Saturday afternoon.

A few hours later, the Commander-in-Chief of the Russian Armed Forces appeared in Moscow’s Cathedral of Christ the Savior. Vladimir Putin lit a candle, crossed himself and listened to Patriarch Kirill. He spoke of the “victory of light over darkness”. Not a word about the war.

It was the eve of Orthodox Easter, the most important holiday for all believers in Russia. Nothing should spoil him. The weeping of the bereaved in Odessa did not reach Moscow anyway – officially, the Russian army only uses “high-precision weapons” designed to avoid civilian casualties.

Now what’s next? When will this nightmare end? In search of answers for the future, one could look to Russia’s recent past, to the Russian war in Afghanistan. Of course there are countless differences, but what unites the two military operations is their futility and brutality.

Top jobs of the day

Find the best jobs now and

be notified by email.

Even then, in the early 1980s, the communist propaganda could not explain to any mother what had brought her son to far away Kabul and why he did not come home in the end, but the “Cargo 200”. In Russian military jargon, this is still the name for the zinc coffins in which soldiers’ corpses are brought home.

Even historians close to the state do not deny that the Afghan war hastened the death of the Soviet regime. From 1979 to 1989 at least 15,000 Soviet families received their “Cargo 200”. In 1991 the USSR collapsed.

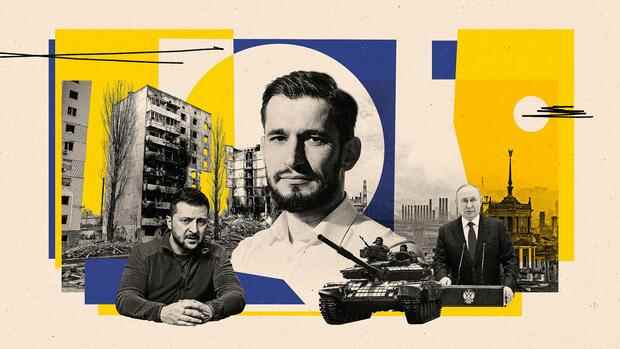

While civilians were dying in Ukraine, the Russian President heard a sermon on peace.

(Photo: Reuters)

In the Ukraine war, Russia is said to have lost more than 20,000 soldiers. These are assessments of the government in Kyiv. The Russian Defense Ministry, on the other hand, has not reported any casualties for more than a month – apparently in order not to spread panic.

But many relatives of the deceased feel neither panic nor doubt these days. At the posthumous awarding of the order “Hero of Russia” to Lieutenant Vladimir Sosulin in the Ivanovo region, his mother spoke sadly but confidently: “Our family supported the special military operation from the very beginning. We knew our son would attend. We have great respect for Vladimir Putin. And don’t let the West attack us and incite against us. It will only make us braver.”

There are almost fairytale ideas about good and evil that you hear from your fellow citizens in Russia. Typical thought patterns: “I don’t know why the war started in Ukraine, but what is certain is that there are fascists there.” Or: “We had to attack Ukraine because NATO planned to attack us.”

No one needs to be a sociologist to realize how irrational these statements are. That’s exactly what the arguments on TV sound like. And almost word for word, they are passed on by viewers without them thinking about their meaning.

Always a new goal ready

In the two months in which Russians suffered defeat after defeat, Moscow has repeatedly redefined the official goals of the so-called military operation. Sometimes there was talk of protecting Russia from NATO, sometimes of protecting the inhabitants of eastern Ukraine from Kyiv. Then it was again about the demilitarization and “denazification” of the whole Ukraine.

In mid-April, Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov drew a line under all the statements: the goal now is to end US dominance in the world. That too sounded more than convincing to the majority of the Russian audience.

It is already difficult to say whether Russian society is just a consumer of this propaganda or also its “client”. After all, the state media would not have been as popular if their hatred and contempt for Ukraine did not match the worldview of most Russians.

This war, this post-Soviet resentment and the longing for belonging to a great power are distracting many from their meager everyday life. Why take responsibility for your own family or even for the country’s economy when all of these hours are being decided in faraway Ukraine? Thousands of coffins from Ukraine also have little effect on the mood.

Russian successes like in the Ukrainian port city are essential for Putin’s propaganda.

(Photo: AP)

In addition, the majority of the soldiers who died came from destitute Russian towns and villages. Tragic local news rarely goes beyond the province. The rest of the country shows with patriotic motorcades, pop concerts or obedient silence that it is ready to fight on.

But how should this end look like? According to sources close to the Kremlin of the Russian Internet newspaper “Meduza”, hardly anyone close to Putin understands how his voters should be taught that the war should end.

After years of hate speech against Ukraine on television, the Kremlin is concerned: How can this popular anger die down without turning into disappointment with its own head of state? What can you present to the country now as desirable war trophies? Like the eastern Ukrainian city of Mariupol? But what about the other parts of the self-proclaimed People’s Republics that are still controlled by Kyiv?

>>> Read here: How Russia is waging its propaganda war in Latin America

On the one hand, nobody has the answers to these questions. On the other hand, the already exhausted Russian army must not return home without some victory. No victory would mean defeat. In the eyes of his supporters, President Putin cannot be defeated.

The very way in which Moscow justified the invasion of Ukraine at the end of February made it clear that the Kremlin chief – like many dictators before him – was a victim of his own propaganda. Apparently, Putin was sure that his army would be greeted with flowers and dances in gratitude for the liberation from fascism in Kyiv.

At the end of April he apparently does not see a worthy way out of the catastrophe. It becomes clear that the President not only believes in his own propaganda, worse still: he fully subscribes to it. Because the return to reality is life-threatening for him.

More: Journey to the Russian hinterland: Where Putin’s propaganda works

The Russian journalist Konstantin Goldenzweig writes the weekly column “Russian Impressions” for the Handelsblatt. The 39-year-old was a correspondent in Germany for various Russian TV stations from 2010 to 2020. He recently worked at Dozhd, the last independent Russian TV station, until it had to shut down. In March 2022 he fled Moscow to continue working in Georgia – like many of his Russian colleagues.