Munich. State aid yes, but not under these conditions: the planned billions in subsidies from the European Union (EU) are welcome in the chip industry. However, the associated interventions in business are met with rejection. Company representatives are quietly warning against a “planned economy”.

There are subsidies for investments in new, highly modern factories or in advanced production processes. The best-known investor is Intel. The Americans should get almost seven billion euros for two factories in Magdeburg. In order to meet the obligations, Intel will not only produce on its own account, but also work as a contract manufacturer for competitors.

At the same time, the Commission wants to monitor the supply chain. In this way, faults should be detected early in the future and a lack of chips, as in the past two years, should be prevented. Brussels also wants to intervene if the chips threaten to run out. In the future, the EU could instruct chip companies which components they have to produce, in what quantities and over what period of time – and at what price.

Top jobs of the day

Find the best jobs now and

be notified by email.

For expert Kleinhans this is nonsense. “The focus is on eliminating short-term delivery bottlenecks. But that is impossible. Because the production takes far too long.” It usually takes between four and six months to manufacture a semiconductor.

EU wants an X-ray of the chip industry

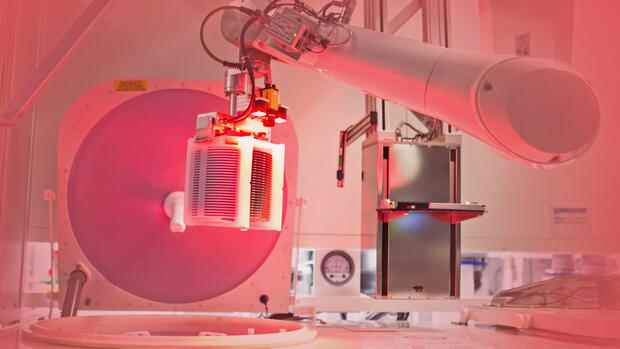

The plans are part of the Chips Act presented by Commission President Ursula von der Leyen earlier this year. The EU Parliament is currently deliberating on the law. The goal is to double Europe’s share of global chip production from under 10 to 20 percent by the end of the decade. At the same time, Europe is to develop more chips and the supply of domestic industry is to be secured.

>>Read here: Billions for new factories: Infineon increases the pace of investment

The EU plans to collect extensive data. This includes whether raw materials, chip machines and workers are sufficiently available in the semiconductor industry. The bureaucrats want to determine the needs of customers broken down by chip type. The community wants to record strong price fluctuations and estimate the effects of natural disasters, customs duties or takeovers.

The individual states should collect the information and forward it to a newly created European Semiconductor Board. It reports to the Commission.

Kleinhans believes that this is based on the assumption that fluctuations in demand and impending shortages can be predicted better than the industry. However, it is hardly to be expected that the chip manufacturers will release sensitive data. You would have no guarantee that these would not fall into the hands of the competition.

>>Read here: The world’s largest manufacturer promises more chips for car manufacturers – but only at higher prices

The EU sees it differently. “We do not ask for confidential data,” said Thomas Skordas, Deputy Director General Connect. Their boss, Commissioner Thierry Breton, pushed ahead with the Chips Act. Skordas: “Rather, we want to know if there are problems.” The electrical engineer warns: If the EU’s chip funding fails, the share of global production will “fall to four to five percent by 2030 – in the best case”.

Industry rejects export controls

Kleinhans, on the other hand, believes that it is unrealistic for the EU to predict demand more reliably than companies or market researchers. That is not all. There are many thousands of different chip types. According to a statement by the Federation of German Industries (BDI) on the Chips Act, a component that was developed for one industry cannot easily be used in another.

“Furthermore, chip fabs are only able to produce a certain range of node sizes and transistor technologies.” Therefore, it is difficult to force a fab to switch from one type of semiconductor to another. It is also unacceptable to impose fines on companies that provide incomplete or no replies to the Commission’s request for information.

According to the BDI, the export controls planned by the EU should also be dispensed with. The European chip industry and its customers would be better off if politicians ensured open markets – and thus better access to critical materials from overseas. In addition, it is desirable for politicians and industry in Europe to work together to ensure that the supply chain is as seamless as possible.

Chip expert Peter Fintl from the consulting firm Capgemini, on the other hand, considers the EU’s plans to be understandable. “The EU is preparing for this if push comes to shove. This ensures the ability to act in an emergency.”

Corporations that don’t accept subsidies needn’t worry too much about someone interfering with them. According to the EU, in the event of a crisis, those manufacturers who benefit from state aid would be obliged to do so.

More: The race to catch up with chips threatens to fail – the future of German industry is at stake