Dusseldorf If doubts arise about the credibility of their sustainability promises, companies can quickly lose sales. This is shown by a survey by the Nuremberg Institute for Market Decisions (NIM), which is available exclusively to the Handelsblatt. 72 percent of those surveyed stated that they avoid companies that are accused of making false statements about climate protection.

“This is a real dilemma for the companies,” says Andreas Neus, Managing Director of the NIM. “Consumers are already punishing them if they are only accused of greenwashing.” The non-profit institute, which is also one of the shareholders of GfK, surveyed 8,000 consumers in eight countries for the study, as well as 800 decision-makers from companies.

The respondents in the study stated that they were generally strongly guided by promises of sustainability, two-thirds prefer to buy from companies that advertise with them. But they have precise criteria by which they judge the credibility of a company.

For 76 percent of those surveyed, it makes promises of sustainability more credible if companies publish calculations on which they are based. External certifications are just as effective. The cooperation with environmental organizations also underlines the honesty of the commitment to the climate for 71 percent.

One thing, however, does not work in Germany: advertising for sustainability with celebrities. A mere 23 percent of those surveyed in the NIM study stated that this made the promise more credible for them. Nevertheless, 38 percent of the companies surveyed rely on the use of well-known people in sustainability communication.

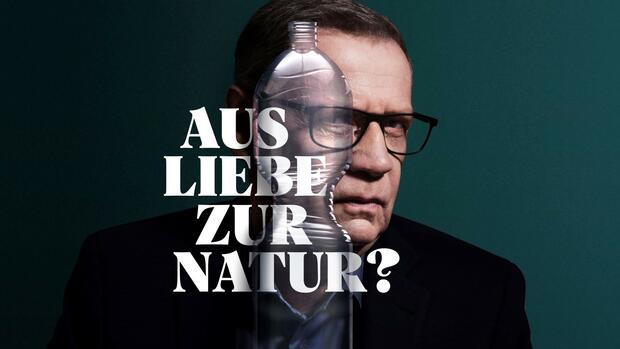

Lidl has now experienced that prominent support is no help when in doubt. With TV star Günther Jauch, the discounter has advertised that its disposable plastic bottle is more climate-friendly than a reusable glass bottle. It wasn’t just a shit storm on social media that followed – against Lidl and against Jauch. The German Environmental Aid has now also filed a lawsuit against Lidl.

>> Read also: Lidl is resisting the introduction of an obligation to return drinks

What has largely gone unnoticed: Lidl had previously met the most important demand from consumers and the EU Commission and had a report drawn up by the renowned Institute for Energy and Environmental Research (Ifeu), which confirmed the statements made by the retailer on the ecological balance of his plastic bottle. That is why Lidl has now also taken legal action against the allegations by German environmental aid.

Foodwatch puts Hipp, Granini and Aldi in the pillory

The backpack manufacturer Got Bag experienced how brutally customers punish companies whose credibility is called into question. In an Instagram post, he advertised that his backpacks were made from 100 percent recycled ocean plastic. But that was not correct, as the company itself had to admit.

After the weekly newspaper “Die Zeit” reported on it last year, a shitstorm broke out over the company. The trust in the target group was gone immediately, reported Mimi Sewalski, managing director of the sustainable online marketplace Avocado Store. Numerous shops took the product out of their range.

The Instagram post in question was several years old, and the company had not advertised with this statement since then. For consumers, however, this was irrelevant. “Every accusation works,” observes NIM Managing Director Neus. Consumers often do not check later whether allegations are correct in detail. This would mean that every sustainability statement would represent an incalculable risk for companies.

The survey of the decision-makers in the 800 companies shows how great the danger for the economy actually is. Half of the companies are already making use of sustainability promises, and another 30 percent are planning to do so in the future. And one in three has already been publicly accused of greenwashing.

The environmental organization Foodwatch, for example, keeps citing examples of what it considers to be false climate promises and calls the compensation of emissions by means of climate certificates “selling indulgences”. In its report “The big climate fake”, the organization pilloried Hipp, Granini, Volvic and Aldi, for example.

EU Commission: Every second environmental statement is misleading

A study commissioned by the EU Commission sees an even higher proportion of false promises. According to this, 53.3 percent of the verified environmental claims in the EU were assessed as vague, misleading or unfounded. 40 percent of the statements were not proven.

That is why the EU Commission is about to pass a directive intended to prevent greenwashing. Companies should be obliged to scientifically prove every environmental statement and have it certified by the state. If they violate this, they face a fine of up to four percent of global annual sales.

The NIM survey shows that many consumers would welcome such an EU regulation. 39 percent of those surveyed demanded that the legislature should set up an independent testing agency that would check all sustainability promises based on scientific criteria. 40 percent would like a state label that is only given to products that are proven to be climate-friendly.

One in three companies has already been publicly accused of greenwashing.

(Photo: ddp/ZUMA)

“Consumers want more clarity,” observes NIM Managing Director Neus. If consumers were given comprehensible and independent information, this could generate sustainable consumer behavior. Even companies like Nestlé would like an official EU climate label.

However, one basic problem remains, even if there were to be a government climate seal. “Many consumers say that they are guided by sustainability, but behave differently in practice,” says market researcher Neus. And that is often due to the price.

Respondents from Germany in the NIM study stated that on average they would be willing to pay ten percent more for a product if it could be shown that it completely avoided or compensated for CO2 emissions. However, the companies surveyed stated that they would have to raise the price by at least 23 percent.

In almost all other countries this gap is smaller. In the USA, those surveyed would even be willing to pay 26 percent more – exactly as much as the companies there have estimated on average for the necessary additional costs.

More: EU makes greenwashing a risk for companies: “Dimensions comparable to the diesel scandal”