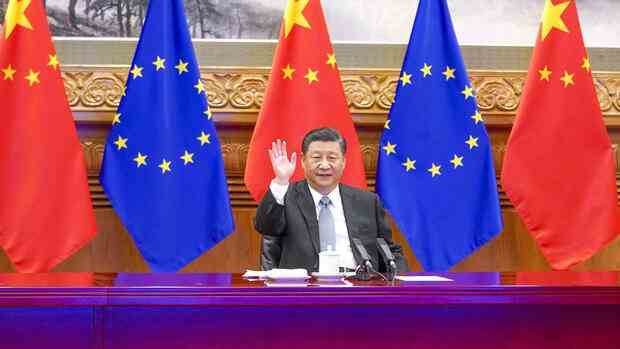

The European countries are trying to make themselves independent of the People’s Republic.

(Photo: dpa)

Finally growing up: Six years ago, French President Emmanuel Macron set the goal for the EU to become completely sovereign, from the economy to defense. For Europe, this became a new source of meaning, at the latest after dependence on China became painfully clear during the Covid crisis.

Since then, the European states have been looking for new partners. Chancellor Olaf Scholz (SPD) recently toured India.

Has the EU come closer to its ambition? The latest trade figures are sobering, at least for Germany.

“In 2022, German foreign trade with China went in the wrong direction at full speed,” writes Jürgen Matthes from the German Economic Institute (IW) in a short study from February. The already high dependency on imports has “increased significantly,” he complains.

No figures for 2022 are available for the EU as a whole. According to Eurostat, however, imports were already well above those before the pandemic in 2021 – and the trend is rising steeply.

The EU’s trade deficit with China is now double what it was ten years ago. Europe gets more than half of its deliveries of machines and cars from the People’s Republic.

One of the reasons for the dependency: Regardless of all the travel diplomacy, the EU is still trying too half-heartedly to find new partners such as the Asean countries with their heavyweights Indonesia, Vietnam, Singapore and the Philippines as a replacement for China. In trade with these countries, Europe is still lagging behind the USA and China.

And trade with Asean countries alone changes little. Southeast Asia is often China’s extended workbench, according to OECD figures on value-added trade. The data does not look at the nominal value of exports, but at the value that is actually generated in each country. In addition, Beijing is often the most important investor in large start-ups in the region.

Handelsblatt author Thomas Hanke analyzes interesting data and trends from all over the world in the column.

(Photo: Klawe Rzeczy)

What would be the solution? IW expert Matthes demands that the EU must help India and the Asean countries “to develop their own value-added basis as quickly and broadly as possible.” Europe cannot force a company that is enthusiastic about China to invest in one of the alternative locations. But it can create optimal conditions for this by concluding trade and investment agreements.

>> Read here: Why Southeast Asia is so important as an alternative to China – but remains a difficult partner for Europe

Some of these have been negotiated for decades. In the case of India, they should be completed in 2023, the EU Parliament is demanding.

The EU acts in a similarly long-winded manner in relation to important partners in Latin America. The agreement with the economic organization Mercosur with the member states Brazil, Argentina, Paraguay and Uruguay should have been concluded long ago.

France in particular is stopping it. Macron, as the most vehement advocate of European sovereignty, belies himself: because French farmers are protesting about a few thousand tons of beef from South America, the French President is holding up the process.

The EU Commission is nevertheless optimistic: “We have accelerated our bilateral agenda in order to open up new markets, contribute to the diversification of sources of supply, but also to ensure stable access to raw materials, other goods and services,” it says Inquiry.

In 2022, agreements were concluded with New Zealand and Chile. “Unfair trade practices” – a euphemism for Chinese subsidies – would be countered in the future. With the Mercosur confederation, she is hoping for “decisive progress this year”.

More: Skepticism about Chinese investments is growing in Europe’s capitals – with one exception