Central banks have relied too much on standard models and for too long have given the impression that they don’t really take inflation seriously.

(Photo: Reuters)

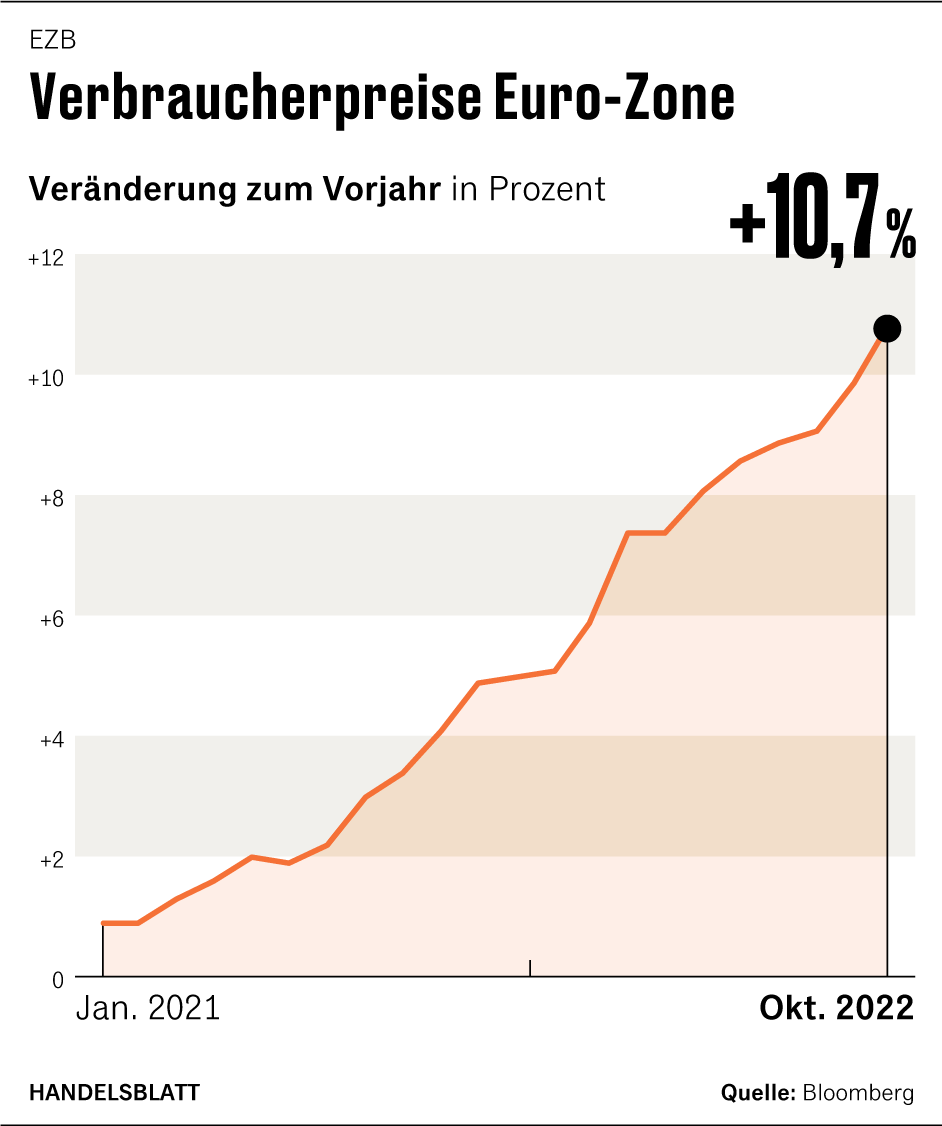

European inflation remains high, it is now well over ten percent. This is anything but surprising: Energy prices have risen sharply and the tightening of monetary policy by the European Central Bank (ECB) is only having an effect with a time lag.

Meanwhile, the economists are arguing. Some say: A central bank can do nothing anyway against a shortage in supply, especially in the energy sector. Others counter that they can dampen demand in such a way that it fits again and prices don’t have to rise.

The debate is particularly relevant for Europe, because here, compared to the US, prices are driven less by demand than by supply.

Sometimes, however, such discussions seem like the judgments of doctors who only see the symptoms and do not understand the disease. Ultimately, the problem is that we have two crises, Covid and war, and have to somehow distribute the consequential costs. The chosen solution is: We spread it as widely as possible – through inflation – and stretch it out over the years – through higher national debt.

Top jobs of the day

Find the best jobs now and

be notified by email.

This can be seen as wrong or dangerous, because ultimately keeping inflation under control is anything but trivial. But the question is always: What would be the alternative? Anyone who does not comment on this is basically refusing to understand the problems in their entirety.

Rather risk higher unemployment?

Would it have been better to massively suppress demand right from the start and keep government finances together? Then the costs would have been more concentrated in the current year and would have appeared in individual sectors, companies and employees. Some of the risks, for example of inflation taking on a life of its own, might have been dampened – but in return there might have been serious damage elsewhere that could hardly be repaired. In any case, the economy would have been given less time to adapt to the scarcity, for example to find new sources of energy.

Everything is ultimately a question of distribution. Anyone who ignores this may overlook the fact that we are still living surprisingly well despite the twin crises – plague and war. Most people still have their jobs, many companies, often smaller ones, have survived long dry spells. It could have been a lot worse.

Does that mean that everything went perfectly in terms of monetary and financial policy? Certainly not. Central banks have relied too heavily on standard models that don’t work well in times of upheaval, and for too long appeared to be disregarding inflation. That has done more damage to their credibility than how late they were in tightening monetary policy.

Incidentally, according to the calendar, the Fed in the USA was the pioneer and the ECB was the laggard.

Measured by the extent to which inflation has become embedded in the economy as a whole and how much it is demand-driven, the Fed has tended to lag behind. A serious debate about monetary policy also started early on in the USA, while in Europe it was primarily those who had been doing this for years without hitting the mark who warned early on about inflation.

The fiscal space has shrunk

A look at financial policy shows that it has achieved amazing things during the corona crisis, also at European level. In part, this has reduced the leeway to spread the consequences of the war, which will still entail enormous financial burdens, through borrowing over the years. There are likely to be even sharper conflicts here, including within the European Union. But seriously, who could expect major crises to pass without mistakes and arguments?

More: The Wealth Illusion – an essay