Dusseldorf Hugo Stinnes? Haven’t heard that name for a long time. Rudolph Havenstein? Who was that? And Kurt Tucholsky? Yes, the great writer. But was he really a banker for a while?

Anyone who would like to refresh their memory or gain insights into these three influential figures in German (economic) history is strongly recommended to read Jutta Hoffritz’s new book “Totentanz, 1923 und seine Folge”.

Almost exactly 100 years ago, Stinnes, the industrial magnate from the Ruhr area, Havenstein, the former President of the Reichsbank, and Tucholsky, the son of a Jewish banker, had to deal with a similarly complex geopolitical situation as it is in Germany and Europe today. The roar of war everywhere, high inflation and gloomy economic prospects put a heavy strain on the three protagonists in their respective work in the early phase of the Weimar Republic.

In fact, 1923 was a kind of economic turning point in Germany: billions in reparations as a result of the Versailles Treaty, steadily increasing inflation figures and the Rhineland is occupied by the French – depression is spreading, in the capital and in the whole large country.

Top jobs of the day

Find the best jobs now and

be notified by email.

Hugo Stinnes, then 52 years old and at the peak of his creative powers, employed 600,000 people in his widely ramified group and is considered the world’s largest employer. His empire includes shipyards, blast furnaces, mines and hotels, such as the renowned Atlantic on Hamburg’s Alster Lake.

Tucholsky was a journalist, literary and theater critic, storyteller, poet, chanson and letter writer. He was one of the most important German feuilletonists of the 20th century.

(Photo: imago images/KHARBINE-TAPABOR)

The rather small man with alert eyes has excellent contacts in politics. And uses them widely. He was already at the table when the government negotiated reparations with the victorious Allies.

Even when the unions later pushed for a socialization of capital. And especially when it comes to pushing back French influence in conjunction with Rhenish provincial politicians.

>>Read here: German Business Book Prize 2022: The winning book combines science fiction and textbooks

All this is also suspiciously registered in (distant) foreign countries. In March, the third or fourth issue of the then just founded “Time Magazine” appears – with Hugo Stinnes on the cover. A merchant from the Rhineland on the cover of the New York news magazine?

Based on his political ambitions, the American journalists write of the “coal king” who is now apparently striving for the “crown of emperors”. It never got that far, but it documents the tremendous influence of Stinne at that time.

In January 1923, top banker Rudolf Havenstein had already been head of the Reichsbank for 15 years. As its president, now 65 years old, the top Prussian official always felt close ties to the Hohenzollerns.

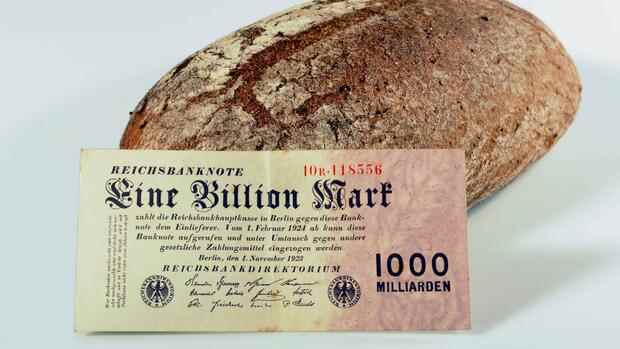

Hyperinflation: black bread for 400 marks

Five years after Kaiser Wilhelm II had heralded the end of the monarchy with his abdication, Havenstein is faced with the most difficult task of his banking career: the man with the high forehead and the twisted mustache has to raise money. Money for the victorious powers and money for defense against the new occupiers on the Rhine and Ruhr.

And he has to fight inflation, so to speak. At that time, a piece of brown bread cost almost 400 marks, and it’s getting more expensive almost every day.

In order to support the exchange rate against the dollar, Havenstein sells gold and foreign currency from the vaults of the Reichsbank, he issues bonds that are also aimed at small savers – all initially without the desired lasting success: the farmers refuse to sell their grain for marks. You want dollars. Or gold. One dollar costs 1.6 million marks these days. And the loaf of bread 69,000 marks.

The then well-known author Kurt Tucholsky, just 33 years old, decided to pursue his career as a writer after bestsellers such as “Rheinsberg. A picture book for lovers”. Despite all his success, his wealth remains modest, and he trades his sharp irony for a position as a trainee at the bank Bett, Simon & Co.

More on inflation:

There, Tucholsky learns everything that an apprentice has to learn: calculate rates, cut coupons, process bills of exchange. He works successfully with his clientele with his wit. The bank recognizes his talent, he rises quickly and his salary is adjusted daily for inflation.

At the same time, his old clients from the publishing houses tried to persuade him to start writing again. Which also succeeds when inflation slowly seems to be getting under control again. Tucholsky resigns from the bank to return to work as an author. But no longer in Germany, he more or less emigrated.

Jutta Hoffritz: Dance of Death. 1923 and its aftermath.

HarperCollins

Hamburg 2022

335 pages

23 euros

Stinnes, Havenstein, Tucholsky: If you want to know how these three extremely exciting lives and careers have developed and many others besides, such as those of the artist Käthe Kollwitz, the dancer Anita Berber or the separatist leader Hans Adam Dorten, Jutta Hoffritz will do it “Book bring pleasure and profit.

After the great success “1913: The Summer of the Century” by Florian Illies, it is another book that describes the history of a single year. At the same time, however, it always goes further, often looking back episodic to the First World War, so that it is not always easy for the reader to always orientate himself correctly in terms of time – perhaps the only flaw in an otherwise successful historical narrative.

More:“Getting to the bottom of things”: what really matters in business books