Frankfurt How hard is half a million words? Around three kilos. Seen in this way, “The History of Investments” by Johannes Seuferle is a massive chunk – and not something to take lightly with you in summer. The former investment banker labored at his work for five years.

To curb euphoria right away: There is nothing for traders and those who want to get rich quick. Rather, the second word of the title, “story”, is also a program.

Those eager to learn with a penchant for enlightenment go on a journey through time. Who has any idea what Demosthenes’ fortune was in ancient Greece in 364 BC? A comparison to common contemporary depots reveals astonishing intersections.

The famous rhetorician and statesman identified, among other things, in a court case: 33 slaves who make swords and knives, raw materials such as wood, iron, copper, the family house, cash, various deposits in banks. The total value came to 76,400 drachmas.

Slaves as an investment have long been done. This also applies to weapons. “But carrying a sword was common among noble people in Europe up until the 17th century,” recalls Seuferle. The stabbing weapon then counted as part of the utility.

Collect what is beautiful and exotic

The philosopher Immanuel Kant distributed his funds differently than Demosthenes. A six percent bank deposit, a mortgage loan on a manor and a stake in a sugar factory have been handed down. In today’s financial slang, we can attest to the clever diversification of the 18th-century Königsberger – and be jealous of the interest on deposits.

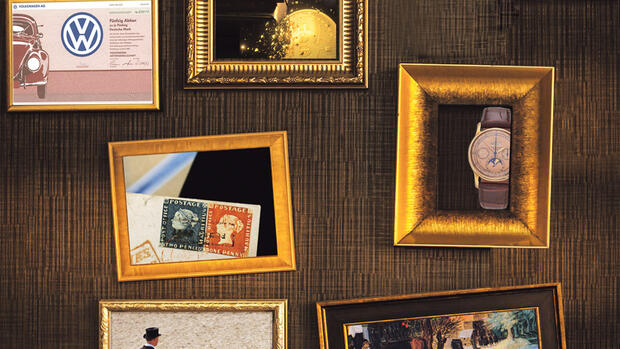

Seuferle’s two-volume monumental work is divided into asset classes. It’s about more than bonds, stocks, real estate, commodities. Separate chapters are dedicated to country, art, other collectibles, alphabetically from Armagnac to cigars.

These chapters invite you to browse. What was and is not all collected. It began with the so-called cabinets of curiosities of the princes in the late Middle Ages. The rulers piled up everything that was particularly beautiful, unusual or exotic.

Shells, precious stones, maps, clocks, tabernacles, chess pieces, astronomical devices, music boxes, coins and much more were coveted. With the exception of coins and precious stones, there were no functioning secondary markets for these objects.

From the 17th century, paintings in the cabinets of curiosities became more and more valuable. The year 1840 brought an invention that immediately created a new field of collecting: the postage stamp.

To this day, some people are very passionate about collecting stamps.

(Photo: imago images / Schöning)

In Seuferle’s history, the reader will find answers to questions rarely asked in other financial histories, such as: How high was the rental yield on houses in the Middle Ages, how did the price of silver develop in the years when gold was banned from 1933 to 1974, how did people invest in infrastructure in the past?

Some goods only acquired the character of investments over time – or lost it. The last group includes slaves and weapons. There were always completely new investments. What would have happened if, more than two centuries ago, economist Adam Smith had been offered the opportunity to secure an internet domain, put money into bitcoins or carbon pollution rights?

Roads, bridges and canals only became objects of investment when government concessions were granted to collect user fees. And of course the share only came into play when the public limited company was formed. The development went beyond materially tangible things. From the 19th century, even intellectual property became conceivable as an investment: patents, copyrights and trademark rights.

>> Read here: Bitcoin & Co. – What remains of the hype

It’s amazing how much the narrative of financial assets has dominated us in the recent past. The USA sets a good benchmark: Since 1980, the market value of shares has quintupled in relation to economic output.

The result is similar when you look at bonds or credit volume. In such a bloated money world, more and more capital is rushing into investments. Therefore one question becomes more important: What can I learn from history? Little positive, says the author. But it’s enough to avoid the worst mistakes.

“Financial history is full of collective misjudgments that are painful for investors,” recognizes the book author. The herd instinct often has fatal consequences. The bizarre speculation with tulip bulbs in Holland springs to mind. The bubble burst in 1637.

Johannes Seuferle: The history of investment. 2 volumes in slipcase

Westend Verlag

Frankfurt 2023

1187 pages

128 euros (until 15.8.23)

It seems surreal when you read how much an onion of the rare “viceroy” variety cost in the euphoria period: 24 truckloads of grain, eight fattening pigs, four cows, four barrels of beer, 1000 pounds of butter and a few tons of cheese. Some made fortunes from tulips. Many lost everything.

But is there a recipe for success? People like to retreat to industry stars, to investment legends like Warren Buffett. “Most of the star investors in history, if they have only been active for a long time, eventually fail phenomenally,” says Seuferle.

More on investing:

He is reminiscent of Bill Gross, Pimco’s former bond guru. And Cathie Wood, the wonderwoman for disruptive technologies. She made many of her share investors poorer by many billions – as of today.

The success story of Andy Warhol’s pictures is more relaxed to read. He originally only wanted $1,000 for his 32 almost identical “Campbells Soup Cans” in 1962. In the same year they were sold to a gallery owner for $100,000 and acquired by the Museum of Modern Art in 1996 for $15 million.

Such rich-maker stories sound like fairy tales with a happy ending. They exist today too. Anyone who had bought shares in the chip manufacturer Nvidia for $10,000 at the low point of the financial crisis would be a multiple millionaire today.

But here, too, the end of the story has not yet been written. Some experts sense a bubble in the artificial intelligence hype driving Nvidia and other tech companies, albeit not the size of tulip bulbs.

In the end, the future remains what it always was: uncertain. To put it in the words of stock exchange doyen André Kostolany: Anything can happen on the stock exchange – even the opposite.

More: These are the best-selling business books in May