Dalia Marin is Professor of International Economics at the TUM School of Management at the Technical University of Munich and Senior Research Fellow at the European think tank Bruegel, Brussels.

A few months ago, fears of a winter full of deprivation were rampant in Germany. There were concerns about power outages and energy rationing as Russian natural gas was halted and prices skyrocketed. Cities are already planning to convert sports facilities into “heat halls” for the poor and old.

But the cries of Cassandra were contradicted by reality. In the face of the historic challenge, Germany proved more resilient than many had believed.

Now that winter fears have passed, the specter of de-industrialization is coming to the fore again alongside concerns about the bank quake. Hardly a day goes by without warnings about factory closures.

DGB boss Yasmin Fahimi explained that the energy crisis would lead to de-industrialization and mass layoffs. The state-owned KfW banking group found that Germany was “facing an era of declining prosperity”. And the Center for European Economic Research in Mannheim described the Federal Republic as the “big loser” in the global economy.

How do you explain the gloomy mood? Since April 2022, German business leaders have been drawing attention to the danger of de-industrialization again, when German politicians were considering boycotting Russian gas. If it comes to that, said BASF boss Martin Brudermüller, the “destruction of the entire national economy” threatens.

Brudermüller’s warning stood in sharp contrast to the assessment of a group of German economists led by Moritz Schularick. They expected that a Russian energy embargo would cause at most a mild recession.

Apocalyptic scenarios did not materialize

After all, a large economy like Germany, they argued, has many ways to prepare for such a shock, such as by finding alternative suppliers and switching to other energy sources. In addition, the government could intervene and cushion the economic consequences of a boycott. As it turns out, the apocalyptic scenarios did not materialize even after Russian President Vladimir Putin shut down the Nord Stream pipeline.

The federal government actually found alternatives to Russian energy, savings measures reduced gas consumption by 30 percent. Prices have now fallen from 350 euros per megawatt hour in the summer to around 80 euros. There were no blackouts and the drop in gas consumption didn’t even depress industrial production as German companies became more efficient.

Europe’s most important economy has survived what is probably the biggest crisis since the Second World War. The German gross domestic product rose by around 1.9 percent in 2022.

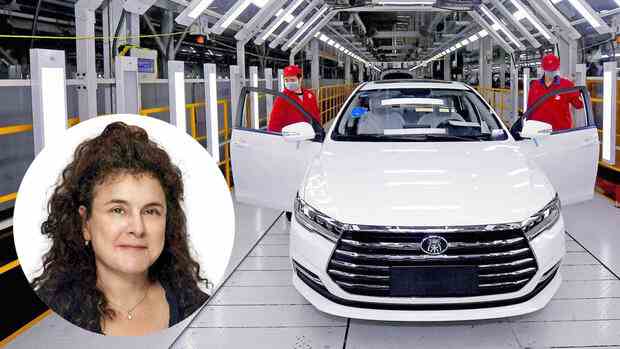

The real threat to Germany as a business location comes from a completely different perspective: China has meanwhile ousted Germany from second place behind Japan in the ranking of the largest car exporters.

Global Challenges – idea and regular authors

From January to August 2022, the Chinese exported a good 1.8 million vehicles, while the German car industry only exported just under 1.7 million. At the same time, China’s auto exports to Europe increased from 133,465 in 2019 to 435,080 in 2021 on growing demand for Chinese-made electric vehicles. Like Germany, Europe now imports more cars from China than it exports.

Germany must reinvent itself again

China’s share of the global electric vehicle market rose to 28 percent last year thanks to its dominance in battery manufacturing and the success of Chinese manufacturers like BYD Auto. In the same period, the share of German manufacturers such as Volkswagen fell from seven to four percent.

In addition to automobile production, Chinese competitors are also threatening German mechanical engineering – and thus the industrial backbone of the country. Chinese exports of machine tools now exceed machine exports from Germany, according to a report published in early 2023 by the Association of German Machine and Plant Manufacturers.

While machine exports from Germany grew by almost ten percent in 2021, the corresponding exports from China increased by 26 percent. Ironically, German companies active in China played a decisive role in the “changing of the guard”: Forced into joint ventures with Chinese partners, they also accelerated the technology transfer to China in mechanical engineering – and thus armed their competitors vigorously.

Germany must now reinvent itself

Germany managed to say goodbye to Russian gas last year without slipping into a recession. But restoring the country’s competitiveness is an even greater challenge.

Three decades ago, Germany transformed itself from the sick man of Europe into an economic engine. In order to be able to survive in the increasingly cut-throat competition of the 21st century, Germany must now reinvent itself.

The author: Dalia Marin is Professor of International Economics at the TUM School of Management at the Technical University of Munich and Senior Research Fellow at the European think tank Bruegel, Brussels.

More: Where German export companies are under pressure