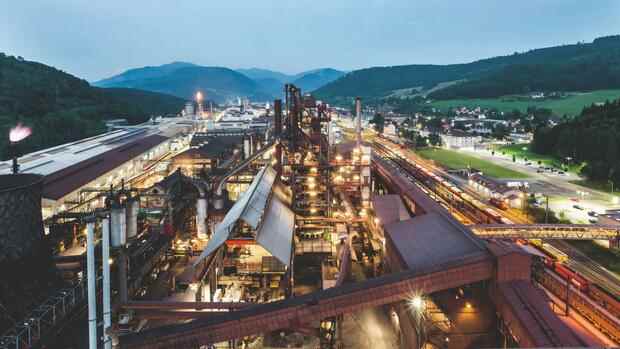

Leoben The plant is smaller than a single-family house and stands somewhat lost on the huge steelworks site in Leoben in Styria. But for the Austrian Voestalpine, the future belongs to it: By 2050, the group wants to produce exclusively CO2-free steel with the help of hydrogen.

The gas that is partly responsible for global warming will then no longer rise from the blast furnaces. Instead, the steel is produced in electric arc furnaces, from which only steam escapes. The plant in Leoben is a test facility that only produces around 70 kilograms of steel in one hour. That is modest compared to Voestalpine’s maximum possible output of 7.8 million tons per year.

Steel production is an example of how big the hurdles are on the way to a green economy. “Metalurgically, it is now possible to produce steel with hydrogen,” says Johannes Schenk, Professor of Steel Metallurgy at the University of Leoben. “But we also need a completely new energy infrastructure.” Scientists and industry representatives unanimously complain that there is no clear plan for this yet.

Voestalpine, a company with 49,000 employees, did not accidentally choose the year 2050 as the turning point. By then, the countries of the EU want to be climate-neutral. How the goal can be achieved is still in the stars. Green steel production is an example of this. “We need completely new concepts,” says Voestalpine CEO Herbert Eibensteiner.

Top jobs of the day

Find the best jobs now and

be notified by email.

In Germany, too, the steel industry is pursuing a plan to replace coal in the production process with hydrogen produced in a climate-neutral manner. For example, Thyssen-Krupp wants to replace its blast furnaces in Duisburg with direct reduction plants and electric arc furnaces by 2045. The Lower Saxony competitor Salzgitter is pursuing a similar strategy, which intends to produce some of the hydrogen required for this itself on its own factory premises.

From an ecological point of view, there is a great deal of leverage in steel production. Around 15 percent of Austria’s CO2 emissions can be traced back to the activities of Voestalpine – and the neighboring countries also contribute to this. German car manufacturers in particular are important customers of the group.

Around 70 percent of the steel produced worldwide is still made using the Linz-Donawitz process, which was co-developed here in Leoben and patented in 1950. In a long process, with the help of the energy source coke, iron ore is turned into pig iron and from it the material steel. This production method is cheap and has proven itself; however, further savings in CO2 are no longer possible with it.

Voestalpine is gradually switching to hydrogen

Steelmaking with hydrogen instead of coal or natural gas would be a game-changer. However, the ambitious project can only be achieved in intermediate steps. Voestalpine will therefore first convert two of the five blast furnaces from coal firing to electric arcs by 2027. Electricity from renewable sources will then be used, but not yet hydrogen.

Over the past hundred years, transport specialists have created an almost perfectly functioning fossil energy system: crude oil or coal can reach remote corners via sophisticated logistics. Now, in ten to twenty years, the economy is supposed to change its mode of production at breakneck speed.

There is still a lack of sufficient renewable energy as well as transport and storage capacities. Not much will change quickly. The approval procedures for high-performance lines and solar and wind parks are not only lengthening in Austria.

For hydrogen to be “green”, it must be produced using electrolysis and renewable energy. But the group managers are wondering where the green electricity is supposed to come from. In Europe, for example, Norway (hydropower) and Spain (solar energy) are possible. “But Europe will hardly ever be able to produce hydrogen entirely itself,” says Franz Kainersdorfer, head of Voestalpine’s metal engineering division.

>>> Be there: Handelsblatt Hydrogen Summit: How does Germany ensure the import of hydrogen?

The amounts of renewable energy required for steel production alone are huge. Scientists have calculated that if all vehicles registered in Austria were to be powered by electricity, twelve terawatt hours of energy would be needed per year.

However, the two Voestalpine steelworks in Leoben and Linz alone require 33 terawatt hours. Around 4,000 additional wind turbines would have to be set up in Austria to supply cars and steelworks with wind energy, says metallurgy expert Schenk. However, there are only 1,300 wind turbines across the country, and in three out of nine federal states there is not even a single wind turbine.

Industry representatives are therefore looking beyond Europe when it comes to green energy. But the further you look around, the bigger the transport problem becomes. A branched pipeline network then certainly does not exist, and liquid hydrogen is difficult to transport by ship.

It is also unclear who will pay for the transformation. Customers are keen to buy CO2-neutral steel. Car manufacturers in particular would like to give themselves an environmentally friendly image. However, steelmakers fear that customers will not be willing to pay a higher price. “We invest a lot of money, but don’t earn more,” says one manager.

Concern about competitiveness also plays a major role here. Europe’s steel industry fears that it will not be able to compete on price with manufacturers from China and the USA, who have to comply with less strict regulations.

Fear of distribution struggles

Investors have already begun to price in the financial consequences. The analysts at Erste Group recently lowered the share price target by ten percent. One of the reasons they cite is the group’s investments of up to one billion euros for the exchange from coal-fired to electric blast furnaces by 2027.

>>> Listen here: Handelsblatt Green: What actually is green steel?

In order to facilitate the upheaval financially, the government in Vienna wants to set up a so-called transformation fund. After a long delay, it is scheduled to start next year. However, it is not yet clear how much money will be invested in it.

In any case, the circle of those entitled to claim will be large: it ranges from energy-intensive industry to small and medium-sized enterprises to boiler replacement in private households, explains the Ministry of Finance. This raises fears in the industry: According to industry circles, many stakeholders would probably try to grab the pot.

The transformation will also trigger distribution battles elsewhere. “Many will want hydrogen as an energy source,” says Schenk from the University of Leoben. “But who shall have it?”

Collaboration: Kevin Knitterscheidt

More: Steel, semiconductors, plastic: the economy is bunkering for fear of supply bottlenecks