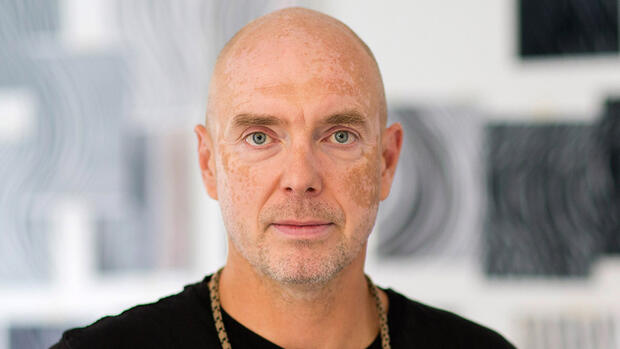

Bonn A device no longer works in the AI and photography exhibition in the Kunstmuseum Bonn. Now Michael Reisch, the curator, has to move in. On this occasion I meet the artist. He’s tall and looks well-trained. You can’t tell that he’s constantly sitting at his computer to do his job.

Mr. Reisch, how do you recognize a work created using digital means?

This is not obvious at first glance. A digitally generated image can have analogue material appearances, eg as an inkjet print, but an analogue generated image can also appear on a screen and look like a digitally generated image there. In any case, for digital works, the question of how they were produced plays a very important role, as this can completely change the meaning of an image.

Could we as viewers see that too?

Since we are still at the very beginning of development when it comes to the new digital tools, we often still lack image competence in this area. That was also a reason for me to curate the exhibition “Expect the Unexpected” at the Kunstmuseum Bonn together with Barbara Scheuermann.

This text is part of the large Handelsblatt special on artificial intelligence. Are you interested in this topic? All texts that have already appeared as part of our theme week

You will find here.

So the artist also has a certain responsibility.

I definitely see it that way for my work. I open up my often very complex work processes and explain very precisely what is done with which tools. As an artist, I see it as my responsibility to enable a fundamental understanding at this point.

What questions does your work raise about the medium of photography?

In my work, I try to question “photography” from all sides and to test the term to the maximum. Does this term still make sense under digital conditions, also with regard to the new digital tools and AI? Shouldn’t we be talking about “photography-based” instead? Do we need new models of understanding?

The exhibition view from the Kunstmuseum Bonn shows a detail of the installation of the same name with 14 AI-generated videos on tablets. The work was created between 2018 and 2023.

(Photo: Michael Reisch)

The question of the truth claim, of the authority of photography has occupied you from the very beginning.

In general, it is important for me to show that photographic and photography-based images are constructions. For me, photography has always been a medium of illusion rather than truth.

The AI discourses are again about the credibility of images. To what extent can we trust them?

At best, credibly contextualised documentary images can still be trusted. Generatively generated images such as those from text-to-image platforms are something fundamentally different and must not be viewed as documents from the outset, but as fictions.

However, generatively generated images can also give the impression of documents, of truth.

This is difficult at this point, since we cannot distinguish between the two on the outside. The real problem is not that digital fakes are possible with AI, but that it is so quick and so easy. Digital fakes can be created in seconds by anyone and everyone and also in all political spectrums.

Do you use NFTs to authenticate your work or does it have an aesthetic purpose?

Tokenization for digital works is in itself a very useful thing because ownership of digital images can be proven. This was not possible before NFT and blockchain.

What requirements do tools like DALL-E and Stable Diffusion place on the market and museums?

(laughs) Nobody knows that for sure. As far as I know, the law in the United States says that no copyright can be claimed on machine-generated images, so this applies to DALL-E, stable diffusion, midjourney, etc. This can cause problems for artists to lead.

Around 2010, the artist had the idea of producing “photographic” images directly from the machine, from the computer, without any reference to the outside world, as a kind of “photography without photography”. Since then, different generations of images, photographs, objects and digital results have emerged from this non-objective, purely digital-algorithmic world, including AI-generated videos on tablets, framed digital C-prints, UV prints on Dibond and fleece wallpaper. You can see the exhibition view in the Kunstmuseum Bonn.

(Photo: Michael Reisch)

How do you assess the AI debate?

The social impact of AI is enormous, it is revolutionary especially for art and photography and will lead to similarly profound upheavals as the introduction of the smartphone and networking, I believe. I see the AI tools for art as an extension, as something new, not as a displacement of classic photographic approaches, both will exist side by side.

And if someone says it’s art?

An AI work must be placed in the discourse and be able to assert itself there – as with painting and traditional media. The fine art categories apply to works by Lucas Cranach, Jeff Wall or Rosemarie Trockel, and also to the new AI-generated images. But since dealing with AI is so new, the uncertainties are great.

Have you ever worked with a program like DALL_E?

Yes, of course, I’ve spent a few nice days with it. (laughs)

Were you able to integrate DALL_E into your work?

Yes. Since I work generatively, I can seamlessly integrate generative diffusion models such as Dall-E 2 into my work processes. But I also take a critical look at the hype, especially with regard to the socio-political dangers and potential of these tools.

The artist used AI to create sculptural structures that were 3D printed and then photographed again, as in this case.

(Photo: Michael Reisch)

You took part in the exhibition “Expect the Unexpected” with your own work. Why did you choose a multi-component installation?

My work is experimental and processual. Around 2010, I had the idea of producing “photographic” images directly from the machine, from the computer, without any reference to the outside world, as a kind of “photography without photography”. Since then, from this non-representational, purely digital-algorithmic world – a zero point of photography, if you will – various, divergent generations of images, photographs, objects and digital results have emerged. This is an evolutionary process, whereby I am particularly interested in the transitions from material to immaterial, from image to object, from the virtual to the physical and vice versa, where the breaks lie, where deformations or unexpected things occur.

What role do system errors, the glitches, play?

Glitches are interesting to me because they make something visible. A photo on the SmartPhone becomes something completely different as soon as it contains a glitch; it then reveals its digital nature. The process of creating the picture becomes visible in the picture, that interests me. At this point, the controlled and smooth, perfect surface is broken, which is normally something that should be avoided at all costs with smartphones. The glitch breaks the hermetic nature of the devices, the programs, deliberately constructed by the manufacturers of the devices. In a way, you can photograph the algorithm, make it visible and penetrate deeper, hidden layers.

With devices like smartphones, you have to stay within the limits of technology.

This question of freedom of action was at the very beginning of my artistic work. It is as old as photography itself and is just becoming very topical again. Who actually takes the picture: photographer or camera, artist or AI? Looking at and critically questioning one’s own tools, the apparatus, is a primal motif for my work.

You described the tech milieu as hermetic. You are dealing with things that, to a certain extent, elude the control of your own horizon of knowledge. Does that affect your work?

I am concerned with the thought that we cannot understand our world, the devices we surround ourselves with, that we are externally controlled at this point. The fact that the large tech monopolies construct their devices in such a way that we as users cannot change the battery ourselves is a form of exercise of power. I also see the disclosure of digital regularities and a basic understanding of algorithmic processes as an attempt to playfully or symbolically break up the balance of power with the means of art.

The compilation of the video stills conveys an idea of the interaction between man and machine. The artist describes it as a continuous interaction in which he intervenes in a controlling manner.

(Photo: Michael Reisch)

Would you describe yourself as an enlightener?

I look at things critically and want to know and understand what’s going on, that feeds into my work. But I see myself first and foremost as an artist and try to elicit interesting new pictorial worlds from the digital world. However, a media-reflective component and a critical questioning are always part of the matter.

Where is the boundary between gimmick and work of art?

For me, play and art cannot be separated. However, if an image or object wants to be included in the canon of art, it has to assert itself in the discourse. Just because something is made with a new technology does not make it art, that applies to AI and VR as well as to pencil and brush.

Mr. Reisch, thank you for the interview.

More: The 1839 Moment – From the Adventure of Artificial Intelligence