Hamburg In the biographies of most German chancellors there is an event that can be interpreted in retrospect as a moment when it becomes clear: someone here wants all the power. In the case of Angela Merkel, it was the guest article in the “Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung” in which she settled accounts with her sponsor Helmut Kohl in 1999. In the case of Gerhard Schröder, it was the night that the young deputy shook the bars of the Chancellery and shouted: “I want to get in here.”

And with Olaf Scholz? The 2018 trip to the G20 finance ministers’ meeting in Buenos Aires keeps popping up. On the flight, Scholz explains to the journalists traveling with him how he imagines his way to the Chancellery: Angela Merkel will no longer stand in 2021, which means an automatic bonus for the candidate with the most experience.

In addition, several medium-sized parties would compete with each other in the election, which means that if the SPD forges the right coalition, it can already provide the chancellor with 20 or 25 percent. One or the other on the plane diagnosed Scholz with an acute loss of reality at this moment.

Not only that, according to Infratest Dimap, the SPD is at 18 percent at this point and has to be asked whether they even want to nominate a candidate for chancellor: Hardly anyone in the Social Democrats sees Scholz as this candidate.

Top jobs of the day

Find the best jobs now and

be notified by email.

The moment of power over the South Atlantic also appears in the biography that the “Zeit” journalist Mark Schieritz is presenting about the new Federal Chancellor. Schieritz: “Scholz told this story again and again, nobody believed him. Until the election.”

Mark Schieritz: Olaf Scholz – Who is our chancellor?

S Fisher

Frankfurt 2022

176 pages

20 Euros

Schieritz’s book comes at the right time, precisely because up until a few months ago hardly anyone thought it possible that Olaf Scholz could actually become Chancellor. Urgent questions need to be answered: Who is this demure Olaf Scholz, who is still a stranger to so many Germans? What drives him?

For the second time since Angela Merkel, the Germans have elected someone to the Chancellery whose motives are not really clear. Unlike the last SPD chancellor, Gerhard Schröder, the half-orphan and son of a cleaning lady, who never made a secret of his hunger for social advancement, his joy in power and his striving for more equal opportunities for German society.

Scholz grew up in a terraced housing estate on the outskirts of Hamburg. In typical taciturnity, he describes his childhood as “beautiful”. And yet somewhere in the Scholz family lies the tinder for a burning ambition: today his brothers are chief physicians and IT managers respectively. Father Gerhard once joked that Olaf, as Federal Chancellor, earned the least of the three.

The parents are enthusiastic about Willy Brandt. Olaf Scholz, now the student representative of his high school, joined the SPD at the age of 17. What follows is a career as an employment lawyer and politician, in which one thing in particular seems astonishing: that Scholz, despite many setbacks, always believed in himself a little more than most of the others in him.

Up to the moment when he loses the race for the SPD party chairmanship in 2019 and many journalists in the capital automatically assume that he will now also resign as Vice Chancellor and Minister of Finance. Scholz doesn’t think about it – and in retrospect it was only the defeat in the party that paved his way to the chancellor’s office. Because the fact that Scholz, who is conservative by SPD standards, is also claiming the chancellor candidacy in addition to the presidency, the Social Democrats would probably never have participated.

From the chaos construction site to the landmark – also thanks to Scholz’s negotiating skills.

(Photo: AP)

But the strength of Schieritz’ easy-to-read biography does not lie in such biographical details. His sources and approaches do not go beyond what many other journalists in the capital could have written about Scholz’s career. Schieritz plays his advantage when he analyzes the Chancellor’s political style and sources of inspiration and classifies him as a typical representative of his age cohort: first a Marxist Juso, then an Agenda 2010 defender … and today?

Scholz has been a bookworm since his school days. “His political work is strongly influenced by his reading,” analyzes Schieritz. The US philosopher Michael Sandel is of particular importance for Scholz’s worldview. Scholz was so busy with his book “From the end of the common good: How the meritocracy is tearing our democracy apart” that he had Sandel connected to a video conference in the middle of the election campaign.

Even under Schröder, equal opportunities were at the core of the social-democratic promise of advancement: regardless of parental home, everyone should have the same opportunities to make something of their lives. Sandel is concerned with what that means in reverse: If you don’t make it to the top despite equal opportunities, it’s your own fault. This humiliation of the social losers promotes the rise of populists who promise: “We’ll take you as you are.”

Scholz makes Sandel’s thoughts his own, in one article the politician writes: The way of life of many “hard-working citizens” is often met with “mocking contempt” in the cultural and economic elites. This can be seen, for example, in the fact that workers in literature, film and science are rarely portrayed with respect.

Scholz wants to resolve this dilemma through a “society of respect” in which every citizen is seen as “an equal among equals”. Broken down to concrete politics, this means, for example: Every gainful job should bring in enough to be able to live on it without public aid. According to Schieritz, the €12 minimum wage, Scholz’s key campaign promise, is a direct result of Sandel’s political philosophy. The same applies to the basic pension promoted by the Social Democrats.

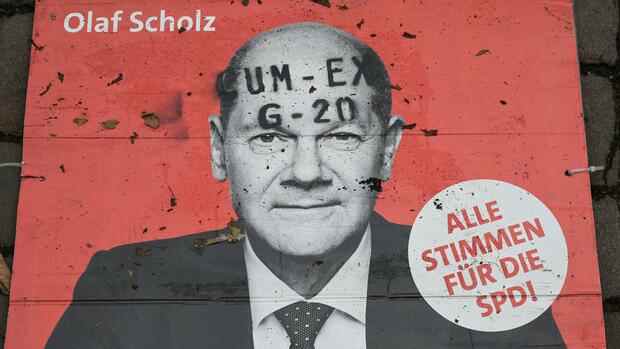

ZFor the second time after Angela Merkel, the Germans have elected someone to the Chancellery whose motives are unclear.

(Photo: dpa)

Of course, Sandel’s theories come from the USA. Can his ideas really be applied to the German welfare state? Does Germany really suffer from too much hunger for advancement – or rather from too much self-sufficiency with the status quo and still far too little justice in educational opportunities? And who really experiences more scorn and contempt in public discourse outside of Hamburg-Ottensen and Berlin-Mitte? The simple worker – or rather the cargo bike-riding academic with a man’s bun?

In any case, Scholz had the right nose. His election campaign, in which he replaced the strenuous social democratic promise of advancement through education with the soft narrative of respect due to all citizens, gave the SPD the election victory. Of course, the two political competitors, the Greens and the Union, helped out with adventurous election campaign glitches.

What kind of Chancellor will Scholz be? Schieritz describes a common characteristic of the politician and lawyer: he relies on the power of negotiations. Bringing all relevant interest groups together and not letting anything get out before a compromise is found: With this strategy, Scholz, as Hamburg Mayor, gets the Elbphilharmonie construction site under control and implements a nationwide exemplary housing program. The traffic light coalition in the federal government, which was forged surprisingly quickly, also bears this signature.

Scholz’s political style has nothing to do with a longing for harmony or even weakness in leadership. Anyone who cannot assert himself in negotiations cannot expect any sympathy from him. Scholz has “the claim to be the top dog, to want to dominate discussions and to leave relatively little room for maneuver,” Schieritz quotes Hamburg Green Party politician Katharina Fegebank, who had to negotiate a coalition with Scholz in 2015. “You have to be extremely rested, ideally prepared down to the last detail, and you have to have a clear idea of where you want to go.”

Only the voters, not the coalition partner, get the respect given to Scholz.

More: Portrait: The resurrection of the Scholzomaten.