On May 9, 2000, the anniversary of the victory over Nazi Germany, Vladimir Putin addresses the Russian people and especially its war heroes. Veterans from Russia, Ukraine, Georgia – from across the former Soviet Union – join the celebrations in Red Square. By today’s standards, they hear an almost unimaginable speech:

“Our people know the value of peace,” says the newly elected President. “We know that peace means strong economy and prosperity. We will pass this most important military secret on to our children.”

Whole generations of children have grown up in Russia since then – and most of the witnesses of the Second World War have died. You won’t hear how Moscow policemen, preparing for the Victory Day Parade, search the apartment buildings along the route of the military columns and ask residents if there are any Ukrainians among their neighbors. 77 years after the end of the war, the day of the victory over fascism has become the day of the new war.

In both Russia and the Soviet Union, on the anniversaries of May 9th, one could learn a lot about the state of society and its political leadership.

Just two years after World War II, in late 1947, Stalin made Victory Day a normal working day again. Great celebrations seemed inappropriate at the time. Too many of the Red Army soldiers saw the sadness of the Europe they had liberated. Half a million war invalids eked out a meager existence, they could neither hope for support from the state nor for a home of their own. For almost every Soviet family, May 9 was considered a day of sorrow and remembrance of deceased fathers, sons, husbands – and not a day of national greatness.

Top jobs of the day

Find the best jobs now and

be notified by email.

Even the sun was made to shine artificially

It was not until Brezhnev came to power in the 1960s that May 9 became one of the most important national holidays. By glorifying the heroic deeds of his generation, the new leader gained political clout, and the stagnant state, turning to its glorious past, sought to duck the future. Most of the rituals around the 9th of May that are still valid today have their roots in this era. Only the rhetoric changed.

The further away from 1945, the louder, more official – and more aggressive this holiday became in Russia.

>> Also read here: Putin and the atomic bomb – How far does the Kremlin chief go?

Most of the now very old veterans could neither take part in the celebrations nor step over the threshold of their dilapidated apartments – there are no elevators or wheelchair ramps in many Russian prefabricated buildings. In return, they received an annual “celebratory” supplement of 100 euros in addition to their average pension of 150 euros. So, with complete satisfaction, they could watch on TV how the Victory Parade turned into a luxurious show of modern military equipment.

The latest tanks and missile systems rolled over the cobblestones of Red Square, the proudest aerobatic teams roared over the Kremlin. In order to further inspire the pathos, this annual march of the victorious people was recorded with more than 50 cameras. In places where they couldn’t be used – for example in the shots from the aircraft nozzles or from the muzzle of a tank – state television commissioned Hollywood-style computer graphics. Even the sun couldn’t be missing that day – several kilometers from Moscow, the Russian Air Force used chemicals to create artificial rain clouds.

Preparations for the celebrations on May 9th are already underway.

(Photo: IMAGO/ITAR-TASS)

In 2014, after the annexation of Crimea and the war in eastern Ukraine, the new militaristic rhetoric was also adopted by schools and even day-care centers. Everyone had to do their part. Shortly before the previous May 9, the five-year-old son of the author of these lines made his first toy tank – from dish sponges, a straw and, of course, at the suggestion of his teachers. The older son, seven years old, a member of a children’s choir, meanwhile rehearsed a song with a lively melody: “Now we bid our defenders farewell to war.”

About five years ago, Russian online shops started selling military uniforms from the 1940s, with replica orders and in all sizes – for schoolchildren or for toddlers. Dressing a child in military uniform was no longer tasteless – on the contrary, for many it was now considered a sign of genuine patriotism.

There were more and more such signs. The windows of many imported cars, including German ones, were decorated with festive stickers for May 9, with slogans such as: “We can repeat that!” (meaning the victorious campaign to the west) or “To Berlin!”. In fact: Every spring, starting in 2015, the Russian bikers from the “Night Wolves” motorcycle club, who are close to President Putin, organized a tour to Berlin.

It was a strange mixture of the old habits of the hooligan scene, wild nationalism and a merciless fight against the “Western enemies of Russia”, which the “Night Wolves” waged mainly on BMWs and Harley Davidsons.

Every civil initiative was suppressed by the state

In Germany, at best, people shrugged their shoulders. In Russia, many felt joy, even euphoria – in a poor, corrupt country there weren’t that many reasons to be proud of what was happening in one’s own country. This militaristic delusion was certainly shared by a large part of society, which by then had long since forgotten the real horrors of war. But the driving force behind it was always the state. What’s more, the government intercepted every bourgeois initiative relating to the culture of remembrance or the history of the war – and appropriated it.

>> Also read here: On “Victory Day” on May 9: Is Putin ordering general mobilization?

In contrast to the saber-rattling of the official state, the journalist Svetlana Mironjuk came up with the idea in 2004 to distribute the so-called “St. George’s ribbon” primarily among young compatriots. At that time, the black and orange ribbon almost fell into oblivion as a symbol of the simple fate of soldiers from the two world wars. Mironyuk’s idea was clear and beautiful: “ordinary” Russians could voluntarily express their gratitude and attachment to their fathers and grandfathers.

But just a few years later, all Russian MPs, TV presenters, teachers, civil servants and ultimately the military people fighting in Ukraine – i.e. everyone who was dependent on the state – had to wear the St. George’s ribbon as required. Nowadays, the nationalized symbol of victory can be found everywhere in Russia: from tie patterns to mayo wrappers.

In 2011, journalists from the Tomsk-based independent local TV2 channel organized a civic action called Immortal Regiment. This was an unofficial memorial march in which several thousand children and grandchildren carried photo portraits of family members who had fought in the war through the city. A few years later, the entire project was taken over and financed by the state. In Moscow, the column of the “Immortal Regiment” was led by Vladimir Putin himself. Only a few noticed that the team of the TV company “TV2” was no longer able to carry out its activities – like most non-state media, the channel was subsequently destroyed.

What is the Kremlin chief planning for May 9?

(Photo: AP)

More: No way back: how Putin became a victim of his own propaganda

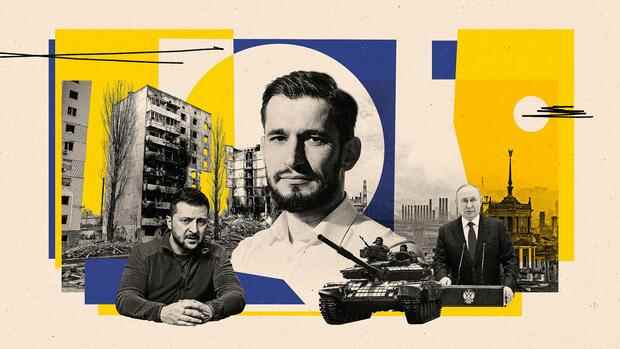

The Russian journalist Konstantin Goldenzweig writes the weekly column “Russian Impressions” for the Handelsblatt. The 39-year-old was a correspondent in Germany for various Russian TV stations from 2010 to 2020. He recently worked at Dozhd, the last independent Russian TV station, until it had to shut down. In March 2022 he fled Moscow to continue working in Georgia – like many of his Russian colleagues.