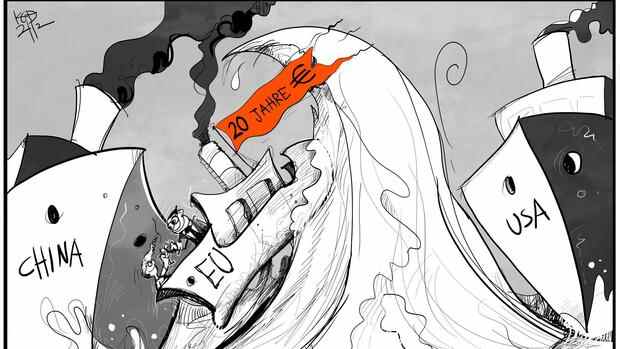

Dusseldorf The euro is alive. This is not something that can be taken for granted. Because from the start, the common currency was a risk that bordered on recklessness. Politically and economically. Europe – this strange structure, somewhere between confederation and federal state, this multi-layered political system with overlapping legitimation structures, gives itself its own currency.

Could that go well? Skepticism was a constant companion of the project. Many American Nobel Prize winners in economics and even the head of the US Federal Reserve, Alan Greenspan, predicted failure quickly. You should be wrong.

Without a doubt, even today, two decades after the introduction of the euro cash, the monetary union is still vulnerable to crises. And yet, the common currency is more indispensable than ever as a symbol of European integration in times of autocratic, nationalist and protectionist self-empowerment.

But the price was undoubtedly high. There were great upheavals, the Greek crisis, which culminated in the euro crisis, global investors attacked the over-indebted countries and tested solidarity. And above all there is a damaged European Central Bank, the institution that has provided obstetrics for the euro for 20 years and is still doing it.

Top jobs of the day

Find the best jobs now and

be notified by email.

Based on an illusion

Trust was shattered, promises were broken. And the most amazing thing: It was foreseeable that this would happen. Because the monetary union was founded from the beginning on the foundation of an illusion.

Mainly under German pressure, the negotiators contractually excluded the liability of the member states for the debts of others. Rescue operations across borders and transfers in general should be kept to a minimum – and if they do happen, then only through the then still very small budget of the Commission.

But that meant that countries with the most varied of competitiveness should be able to hold their own and develop equally economically with the same external value of the currency and with the same interest rates.

Italy, for example, which for decades devalued its lira as regularly and reliably as clockwork against the D-Mark in order to maintain its competitiveness, had to move from one day to the next in a new environment. At best, that could be suppressed for a while because the low lending rates initially triggered a consumption-driven boom. The expectation that the Maastricht criteria – no more than three percent budget deficit in relation to economic output and no more than 60 percent national debt ratio – would create sufficient homogeneity as a condition for joining the Euro Club was an almost negligent assumption.

For political reasons, they turned a blind eye to EU founding member Italy. The obvious trickery of Greece when joining the euro in 2001, the country that later became insolvent and had to be rescued from the treaties in order not to jeopardize the euro as a whole, will also not be forgotten.

American economists predicted a quick failure of the common currency.

(Photo: imago stock & people)

In the end, then, the single currency was nothing more than an attempt to overcome the competitive differences between member states by simply ignoring them.

And so it is no wonder that mechanisms have been developed to at least alleviate the birth defects. Even with the rescue of Greece, the crisis managers circumvented the bail-out ban under the European treaties. This was followed by the European ESM rescue package, which institutionalized the breach of the rules. Later in the pandemic came the “reconstruction fund” of 750 billion euros, for which the Commission can be itself indebted – that too contradicted the treaties.

But once again the need knew no commandment. In the case of the ESM, the approval of the other states was still required when the ESM granted loans to countries in distress. For the Corona Fund, on the other hand, the EU Commission itself takes out loans and sometimes passes them on to EU countries as grants.

The next step is the Maastricht criteria. Because the debt ratios of many countries are well beyond the 100 percent mark, record holders are Greece and Italy (220 and almost 160 percent respectively), the rules are adjusted to reality as usual – and not the other way around.

However, the European Central Bank itself suffered the greatest damage. For almost 15 years it has been in crisis mode and is on the edge of its mandate, some say – not wrongly – far beyond it. Perhaps at some point it will be faced with the momentous decision of either fighting the sharp rise in inflation or holding the euro together.

All of this shows that the monetary union has so far not been able to produce the fundamental prerequisites for its functionality on its own. It was founded as a community of hard currency. In a creeping process, it is now gradually becoming a transfer community that it is not allowed to be by contract. .

The dilemma: what could provide legitimation and legality for the currency community, namely a proper political union with full budgetary power of the EU Parliament and a proper government, is refused by precisely those countries that want a transfer community.

France in particular is persistently resisting relinquishing national sovereignty. That would be the prerequisite for the introduction of the controversial euro bonds and ultimately also for the establishment of the “United States of Europe”.

But as desirable as it is, it is a long way off. As the situation is now, there is no alternative to “muddling through”, which Europe has now developed into an art form. Surrendering the euro, as so many economists in this country carelessly bring into play, would by far exceed the establishment of the monetary union in recklessness. It would be an economic suicide. Despite all the difficulties, the largest economy in Europe is still the big beneficiary of the euro. The euro critics are right, however, when they point out that the difficulties in competition in the southern countries are primarily due to structural reasons. Only reforms can help in the long term; cash transfers at best alleviate symptoms.

In the end, it is also a question of whether we are striving for a debt-driven, statist Europe or a market economy-oriented one. One thing is certain: Europe is fighting for its place in the world in the epochal conflict between the USA and China. The most important prerequisite for this is its unity, and this includes not only, but above all, monetary union.

More: The euro has withstood a lot of criticism – and is still a debt burden.