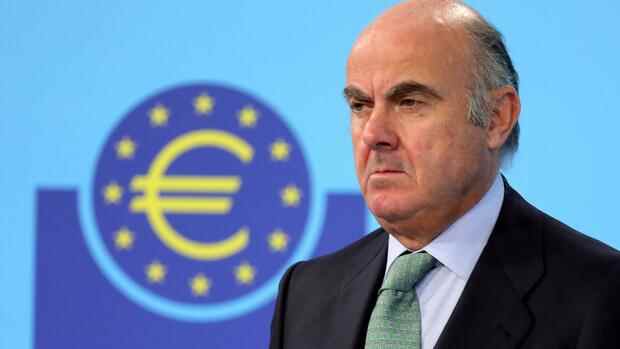

Frankfurt ECB Vice President Luis de Guindos is calling on politicians to do their part to prevent a wage-price spiral. The current price shock in energy and raw material prices is making many companies and employees poorer. “Financial policy should help to reduce the burden through temporary, targeted aid,” he said in an interview with the Handelsblatt.

In his view, the ECB’s future monetary policy course depends on the data: “If we continue to underestimate inflation, then we will react. All options are on the table.” According to de Guindos, the key factors are second-round effects and a possible rise in medium-term inflation expectations. “If we see them, then we will act.”

The Spaniard warns that fragmentation in the euro area due to widely differing interest rate levels on the bond markets could jeopardize the effectiveness of monetary policy.

Top jobs of the day

Find the best jobs now and

be notified by email.

At the moment, however, he does not consider the risk premiums for government bonds from countries such as Italy and Spain to be of concern. They are “currently about as high as before the pandemic” and are “well below the peaks of around 2011 and 2014”.

Read the entire interview here:

Mr de Guindos, how great is the risk that the war in Ukraine will cause problems in the European financial system?

Even before the current crisis, there were risks, such as high valuations on the financial markets and indebtedness in the private sector and in government. But the development today is not comparable to that two years ago when the corona pandemic broke out. There are no liquidity bottlenecks. For example, companies can continue to place bonds. The stock markets are volatile, but we don’t see any dramatic developments at the moment.

But there have been problems on the commodity markets.

In the case of commodity derivatives, there have been so-called margin calls, i.e. additional collateral for open positions. But according to our observations, these additional requirements have so far been met.

What do you think is the greatest threat to the financial system?

The macro risk, i.e. the possible consequences for the economy as a whole. Because higher inflation and lower growth are the greatest risks, also for the banks. This plays a much more important role than problems in individual market segments.

Are we now moving towards stagflation, i.e. a situation of weak economic activity and high inflation?

I would not say that. Before the war broke out, we assumed four percent growth for the current year and a little less for next year. In our most recent forecasts, even in our worst scenario for the current year, we still see growth of over two percent in the euro area, so no stagflation. But there is likely to be higher inflation for a longer period than expected before the war.

What role does the recently weak euro play?

We do not target a specific exchange rate. Of course, we acknowledge that certain imports will become more expensive as a result of a weaker euro exchange rate. On the other hand: The currency shift is particularly evident against the dollar, which is still in demand as a safe haven currency. If we take a closer look at the currency basket of our trading partners, we see that the euro has remained quite stable.

There is even speculation that the ECB could intervene in the foreign exchange market.

We do not intervene in the foreign exchange market because we do not have an exchange rate target.

Inflation has risen significantly recently. Can the ECB keep prices under control at all?

What matters to us now is how strongly wages react. Because if the increases are too high, it can drive up prices even further and contribute to permanently higher inflation. So far we haven’t seen any signs of this, but we have to keep a close eye on developments. The same applies to inflation expectations. Based on surveys and market data, expectations are anchored close to our inflation target of 2% for the next three to five years. But we have to keep that in mind.

Last week, the ECB announced that it would end its bond purchases more quickly. What does this mean for possible rate hikes?

The key decision in our session was to decouple the potential rate hikes from the bond program, they will not have to happen automatically after the purchases are halted. In this way, we keep all options open to react flexibly to the data.

Does that mean the first rate hike will come later?

It all depends on the data. We are closely monitoring inflation developments. We will be extremely vigilant for second-round effects and for developments that point to a wage-price spiral, where the two factors are mutually reinforcing. Fiscal policy should also make its contribution here.

What do you mean exactly?

The price shock for energy and raw materials that we are currently experiencing is making many companies and employees poorer. Fiscal policy should help reduce the burden by providing temporary, targeted aid. This would also reduce the risk of a wage-price spiral.

Do last week’s decisions really amount to a tightening of monetary policy?

I would say it’s normalization.

According to the ECB’s own forecasts, inflation should fall back to around two percent in 2024. Why should this happen so suddenly?

Forecasts are particularly difficult at the moment. One reason inflation is easing may be that the sharp rise in energy prices cannot continue for too long. Although prices can stabilize at a high level, they can no longer continue to rise at the same rapid pace as at present.

In the past, the ECB has always overestimated inflation, and recently it has tended to be too low. Is there a problem with the models on which the forecasts are based?

We underestimated inflation last year, as did other institutions and economists. Forecasts are particularly difficult in times of great uncertainty. Past trends play an important role in the models. Models tend to return forecast inflation levels to historical mean values.

But what will the ECB do if it continues to underestimate inflation?

Our decisions are based on the data. If we continue to underestimate inflation, then we will react. All options are on the table. The key factors are second-round effects and a possible unanchoring of medium-term inflation expectations. When we see them, we will act.

The ECB will ensure that monetary policy is implemented smoothly.

(Photo: dpa)

In Germany, there is great concern that the ECB will not be able to take a hard line against inflation because of the high level of debt in countries such as Italy and Spain.

Our monetary policy is entirely driven by our mandate of price stability. Our monetary policy decisions and available instruments are aligned with our inflation target. Fragmentation in the euro area, for example due to widely differing interest rate levels on the bond markets, could jeopardize the effectiveness of monetary policy. However, the risk premiums on government bonds from these countries are currently about as high as before the pandemic. They are still well below the peaks in around 2011 and 2014. In addition, nominal yields are still very low overall.

But weaknesses in the construction of the euro zone have repeatedly emerged in the past. Are the ECB’s instruments sufficient to keep risk premiums within limits if they widen?

We have the opportunity to counteract this in a targeted manner through flexible reinvestment of the expiring bonds under the PEPP emergency program. But we must clearly separate this flexibility from the general monetary policy objective. Our task is price stability.

Wouldn’t it be the task of fiscal policy to keep the euro zone together?

Fiscal policy undoubtedly has an important task. It must purposefully compensate for the hardships resulting from today’s crisis. It is also targeted and temporary so that the volume of this aid does not drive the national debt much higher.

Where should this happen, at national or at European level?

First at national level, but a coordination framework at European level should be agreed.

More: Bundesbank boss Joachim Nagel: “We are experiencing a turning point”