Vienna At times, Ukraine appears almost uncannily closed to the outside world – and yet politics has not been abolished. Even if the fight against Russian aggression is a national consensus, power struggles and social problems have not disappeared. They just appear in a new form during war.

The dispute between Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky and Kiev Mayor Vitali Klitschko is an example of this. The primary concern was that many of the warm and sheltered rooms for the population – pompously dubbed “places of invincibility” by the president’s office – are not in operation. The problem is causing considerable dissatisfaction among Kievans, who have been severely tested by Russian airstrikes.

Even though the planning of the rooms is the responsibility of the president’s office, which, according to media reports, proceeded in a rather uncoordinated manner, Selenski quickly found a scapegoat in the power-conscious Klitschko. The former boxing star was not only considered a confidant of Zelensky’s rival and predecessor Petro Poroshenko, but also reluctant to be talked into city affairs.

Under the prevailing martial law, the army leadership would have the authority to put him under a military administrator. But Klitschko does not accept this, and the President has so far refrained from escalating the conflict. This has a lot to do with Klitschko’s popularity, but also with observations from abroad.

Top jobs of the day

Find the best jobs now and

be notified by email.

It was no coincidence that the mayor immediately turned to the “Bild” newspaper with his concerns, with which he has close ties. Zelensky, on the other hand, does not want to damage his image as a defender of Western values with open, politically motivated attacks on the opposition.

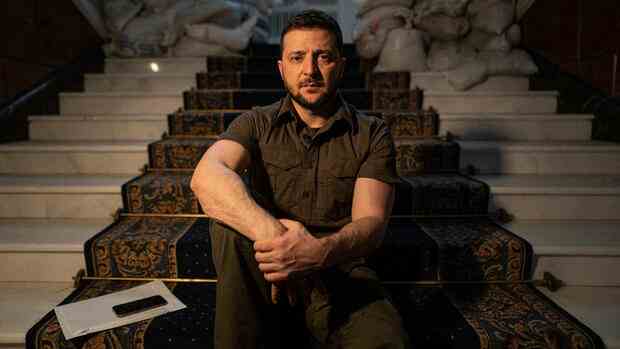

The mayor of the Ukrainian capital has resisted attempts by Zelenskiy to interfere in his affairs.

(Photo: Reuters)

At the same time, Moscow immediately presents any dissonance in Kyiv as a fault line in the national united front. Therefore, in order not to provide ammunition for enemy propaganda, Ukrainians avoid controversial issues. The culture of domestic debate is largely paralyzed.

This affects, for example, the parliament, the Verkhovna Rada. It has been working on the back burner for months for security reasons, but has hardly shown any other initiatives. The parliamentarians are primarily concerned with implementing the rapprochement with the EU through legislation – a topic that is undisputed domestically.

The opposition in Ukraine is fragmented

Zelenski’s party essentially nods to the executive’s proposals and also has a problem mobilizing its own deputies, since parliamentary work has little priority in the government bloc. Paradoxically, the presidential party is receiving support from the once-pro-Russian forces. The opposition is too fragmented to take countermeasures.

The Verkhovna Rada is working on the back burner.

(Photo: IMAGO/ZUMA Wire)

The war offers opportunities for profiling – not only for the president. Political observers place the likely leaders of post-war politics in either the government, the armed forces, or voluntary organizations. They all have considerable social prestige and often hover above everyday political business.

Commander-in-Chief Valery Zalushni is mentioned as a potential future competitor for Zelensky, as is former TV presenter Serhi Pritula, who collected the equivalent of more than 40.5 million euros in donations for the armed forces through a fund named after him. “I’m not a politician. I’m a volunteer,” he emphasizes, although he takes advice from a well-known image expert and does extensive PR.

Even though the next presidential election isn’t scheduled until 2024, Zelenskiy is apparently taking steps to put himself in an even more favorable position. According to the online newspaper Ukrainska Pravda, the presidential office has at least partially taken control of the media empire of the controversial oligarch Rinat Akhmetov, who gave it up under political pressure in the summer.

Critical media hold back

The resulting channel “Wir sind der Ukraine” had received a license in record time, which the newspaper said would have been impossible without support from the very top. The transmitter is now part of those channels that jointly produce the so-called standard news. Parliament recently made available the equivalent of 50.7 million euros for the coming year, a large sum in the war-torn Ukrainian media market.

More Handelsblatt articles on the war in Ukraine:

Even if critical media continue to maintain their control function, they only approach sensitive issues very cautiously, especially when it comes to abuses in the military or corruption in aid deliveries – often more out of self-censorship than direct political pressure. Research like that of the “Kyiv Independent” on the disastrous conditions in the so-called International Legion remain the exception.

However, strong independent media are becoming increasingly important. War creates a growing sector of state activity that, while understandably secret, is also prone to shady dealings, especially in a country where corruption is rampant.

A month ago, for example, the government subordinated five strategically important large companies to the Ministry of Defense as part of its martial law powers, including the oil company Ukrnafta and the truck manufacturer Avtokras.

The business magazine “Forbes” estimates the assets taken over by the state at almost one billion euros. The modalities remain unclear. Officially, the affected oligarchs should get everything back after the end of the war. As long as this lasts, they will be disempowered – another example of the executive branch expanding its power in a gray area.

More: Zelensky under pressure: domestic political unity in Ukraine is shaky