Frankfurt Everybody sees everything. The data group records and evaluates the thoughts and actions of each individual – and praises or stigmatizes them. Delaney Wells, the main character in Dave Eggers’ new novel “Every”, declares the fight against the dictatorship and joins the company.

Your thought: At some point, people would have to resist increasingly oppressive apps. Too bad that doesn’t happen. On the contrary: the desire for transparency and control seems insatiable, security beckons like a place of longing.

Eggers gives us little hope in “Every”. In his almost 600-page work, the American author continues the surveillance vision of his predecessor novel “The Circle”, published eight years ago. Everyday life has become public.

You can only smile at the first moment when the loo-visitor wants to leave the toilet but cannot get out. Without washing your hands for at least 20 seconds, the door stays shut. Cameras and sensors capture life almost completely in images, sound and text. Right down to eye tracking. Who is looking where can be tapped with the iris scan of a camera.

Top jobs of the day

Find the best jobs now and

be notified by email.

When a man gazes at a woman, the eyes are blindfolded with the perpetrator’s name and his family, employer, and the public can be informed. And preventive measures are taken against domestic violence. As soon as the sound in the house becomes rougher, the sensors sound the alarm and the police arrive. That even affects Delaney’s parents.

Dave Eggers: Every.

German translation: Klaus Timmermann, Ulrike Wasel.

Kiepenheuer & Witsch

Cologne 2021

592 pages

25 euros

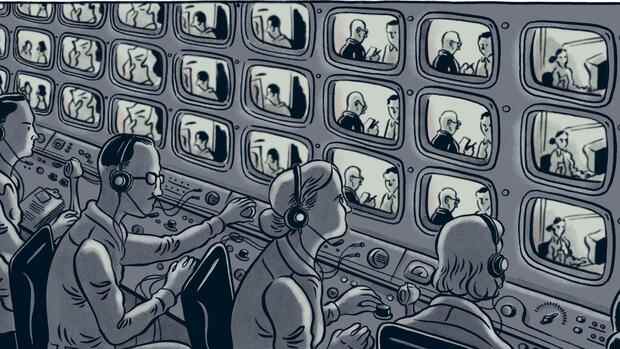

Many things from Eggers’ fiction are already close to reality – and are very reminiscent of Georg Orwell’s groundbreaking dystopia “1984”. In it, Winston Smith works in the Department of Truth, where he rewrites the history of each individual as the government decrees. Everything is nicely observed and monitored by the “big brother” and the thought police. “1984” has just been released as a finely drawn graphic novel that provides a new, gloomy approach to a highly explosive topic.

Today it is the big corporations on the Internet that act as Big Brother and Thought Police. Facebook, Google and whatever their name is, they know everything about their users. And use this data to your advantage. The central question that arises today when it comes to this topic is: How do we stay in control in the digital world? Not only Eggers and Orwell deal with this, but also several non-fiction books.

George Orwell: 1984. Graphic Novel. Adapted and illustrated by Fido Nesti.

Ullstein

Berlin 2021

224 pages

25 euros

Gerd Gigerenzer makes the question of control the subtitle of his new book. The short, striking title: “Click”. The bestselling author is a risk researcher. So it’s not surprising that he worries most of all. About the future of the individual in a world of internet corporations. About the incapacitation of the individual, the loss of control, just as Eggers imagines.

The corporations collect data, the governments appreciate it. That is the unsavory vision of the professor of psychology and behavioral science. He also sees the foundations of the democracies attacked. One feels reminded of “The Age of Surveillance Capitalism” by the economist Shoshana Zuboff.

Gigerenzer names data octopuses like Facebook and Google with their business models of personalized advertising, fed by user data, as the Urübel. Users get all services for free, pay for them with the traces they leave behind on the Internet.

Gigerenzer describes social credit scores that aim to capture trustworthiness in every respect. China is the cited – and chilling – prime example. The scientist lists the types of school grade that can be collected: speeding tickets for driving too fast, police clearance certificates, volunteer work, neglect of family duties, political statements on social media, websites visited and much more.

How much fear is justified?

Open or hidden, tech companies and government organizations are working together to create a world of total surveillance. So the concern. The author is convinced: “To be observed will be our future – unless the citizens, the legislature and the courts intervene to put a stop to the scoring of the population.” Exactly that does not work in Eggers’ vision.

Gigerenzer stirs up a fear of the new, the unknown, the intangible. Fortunately, he doesn’t leave it at that. In the second step he asks: How much of this fear is really justified? And, above all, where are the solutions?

The expert has a specific idea: At the moment, Facebook, for example, is financed almost exclusively through advertising. So of course the company has to please the advertisers. This cycle must be broken.

With a very simple means: not the corporations, but the people should pay for the services of the tech companies. How much would users have to give to Facebook to compensate the company for the lost revenue? Gigerenzer calculated that it was two dollars a month. He thinks that is a realistic alternative.

Gerd Gigerenzer: Click. How we stay in control in a digital world and make the right decisions.

Publishing house C. Bertelsmann

Munich 2021

416 pages

24 euros

The author expressly warns against dismissing digital transparency as a Chinese problem. Western states like the USA are also ready to tolerate surveillance capitalism. Edward Snowden had already revealed that the government was secretly running surveillance programs with Internet companies.

All of this hardly seems to be enjoyable to read. But it is required reading in a world in which more and more life processes are being digitized at a rapid pace. It is instructive in addition. Gigerenzer is a scientist, but he writes in a generally understandable way. In his 352-page wake-up call manifesto, he likes to expose endeavored Newspeak such as “Big Data”, “Artificial Intelligence”, “Autonomous Driving” and “Smart City” as misunderstandings with a potential threat.

Sarah Spiekermann, Professor of Information Systems and Society at the University of Vienna, denounces similar undesirable developments: surveillance, big data illusion, endangerment of privacy, danger of online addiction. Your title “Digital Ethics” reveals a slightly different perspective. She is looking for ways to protect human values. Freedom, dignity, friendship, community, security, trust are part of it.

The professor speaks of the forgotten philosophy of good behavior as found in the ethical writings of Aristotle, John Stuart Mill or Immanuel Kant. In modern times, the paradigm shift in thinking has turned out to be a disadvantage. Unparalleled technical inventions and scientific innovations have shaped the belief in technical progress. In short: the new is good, the old is bad. And today the new is mostly digital.

Spiekermann uses the example of delivery services to describe how people get lost in this age. The working conditions of the bicycle couriers with low wages, restrictions of freedom, tracking of their journeys remind them of the early industrial exploitation. The machine navigates people. The economy is also heading towards systemic indifference: “We are creating a dehumanized working and eating culture.”

The capture by technology begins much earlier. The business model of the large data corporations requires us to stay on their platforms all the time. In the worst case, we become dependent, addicted. In an interview, a student told Spiekermann that losing her cell phone felt like someone had chopped off her hand. It is reminiscent of the shocking results of an American study: Two thirds of the students surveyed were willing to have their cell phones implanted under their skin.

Sarah Spiekermann: Digital Ethics.

Droemer

Munich 2021

304 pages

19.99 euros

Trapped like spiders in the web, that’s how Spiekermann puts it. It therefore calls for a ban on business models with apparently free digital services that live from our personal attention and our data. In their opinion, the addictive design of such services should be banned, and it should be possible to switch off default settings to ensure privacy.

Spiekermann underpins their warnings with the behavior of the tech icons: Apple’s creative genius Steve Jobs had banned his children from using the iPad that he had just launched. Microsoft icon Bill Gates did not allow his daughter to take calls on a smartphone until she was fourteen. In Silicon Valley, many parents send their children to schools where low-tech such as chalkboards give them a competitive advantage.

So how can you limit the disadvantages of networking while preserving its advantages? Spiekermann suggests, for example, that access to the individual should be slowed down. Some of the ideas: deliver emails only once a day, social media also update their postings only once a day. Education and clarification are important to the scientist: networking costs time and energy, restricts real community, distracts, leads to superficiality and progressive loss of personality.

Spiekermann provokes the reader to look back – and to look forward. We remember: The first computers were room-filling monsters, still far removed from the user. Then the smaller device went to the desks. Today we carry it in a further reduced volume, mobile close to the body. According to this logic, the next step would be to shrink the distance into the body. That also fits in with the aforementioned American study.

The authors demand limits from politics

At the end of this history of progress is transhumanism, which, according to Spiekermann, simply regards humans as a suboptimal obsolete model. The proactive replacement of biological body parts and organs with allegedly more suitable computerized carrier materials stands in the room.

Up to the idea of scanning the brain and simply uploading it to a computer. For Spiekermann one thing is clear: The body is of little importance to transhumanists, for them feeling and intuition are disposable disadvantages of humans, values do not count.

What is required here is the setting of boundaries by politics, the authors agree on this. For Gigerenzer, the EU General Data Protection Regulation is a first step towards regaining lost trust. The European Union is working on two pieces of legislation that are intended to set limits for digital corporations.

She has also already made a proposal on what a good legal framework for artificial intelligence could look like. Systems with an unacceptable risk classified in this way, which manipulate human behavior or are used by authorities to evaluate social behavior, should be completely banned.

As with the “Friendy” app in Eggers’ novel. At the latest, the revolutionary Delaney would have expected protests. Your polygraph analyzes how good or bad friendships really are. Artificial intelligence evaluates all available information, including body language in videos and photos. Billions of lies are exposed. So everyone prefers to censor themselves. Those who don’t participate are socially down through. A horror scenario.

More: From China to the world – totalitarian technology becomes an export hit.