Almost 40 years ago, the fight for shorter working hours served one goal in particular: the feared massive job cuts should be prevented. The trade unions in the metal and printing industry therefore called for the 35-hour week.

In view of the high advances in productivity at that time as a result of rationalization measures, the remaining volume of work should be redistributed to as many employees as possible. After heated arguments, the employers agreed to noticeably shorter weekly working hours.

While the collectively agreed weekly working hours have remained largely unchanged over the past decades, the effective working hours have steadily decreased. The regular weekly working time between 1991 and 2021 fell by 3.7 hours from 38.4 hours – almost ten percent.

Far more significant than the decline in the average number of hours worked per full-time employee has been the marked increase in part-time employment, from 14 percent in 1991 to 29 percent in 2021. “40 hours? No thanks,” was the apt headline in the “SZ” last weekend.

The economist of the century, John Maynard Keynes, had a premonition of this development in 1930, i.e. in the middle of the global economic crisis. He was firmly – but in hindsight erroneous – convinced that enormous advances in productivity would free mankind from economic constraints and worries. He predicted that in the 21st century nobody would have to work more than three hours a day or 15 hours a week to be able to fulfill their dreams.

Labor shortages are worsening

In fact, despite computerization and digitization, productivity growth has been very weak in almost all industrialized countries over the past three decades. In Germany in the pre-Corona year 2019, labor productivity per employed person was just under three percent higher than in the pre-financial crisis year 2007.

This raises the question of whether Germany’s rapidly aging population can really afford to continuously reduce average gainful employment without relevant productivity growth.

doubts are warranted. As a result of the imminent demographically induced decline in the overall economic labor supply, a more than 15-year-long decline in trend growth, which is currently just under one percent, is predicted.

The Handelsblatt Research Institute (HRI), in line with the other economic research institutes and the federal government, assumes that the all-time high in employment will likely be reached in 2023 or 2024 at almost 46 million, and then decline by 130,000 people per year. The already obvious shortage of workers will therefore become significantly worse in the coming years and decades.

>> Read here: Lack of staff causes almost 100 billion euros in lost value

There is no panacea for counteracting this anti-growth trend. The often-demanded extension of working life would come too late, since it could not be implemented until after 2031 at the earliest, when the standard retirement age of 67 years was reached. In view of the increasing life expectancy, such a step could be well justified, but would be tantamount to political suicide for any government, since a further increase in the retirement age is very unpopular with the aging electorate.

The annual net immigration of 400,000 workers that is also propagated – which would correspond to gross immigration of a good 600,000 people – is illusory. Nobody knows where these qualified workers are supposed to come from, where they and their families live and how they can be integrated into society without conflict. Moreover, most industrialized countries are vying for qualified immigrants, and the German language acts as a high hurdle for many potential workers.

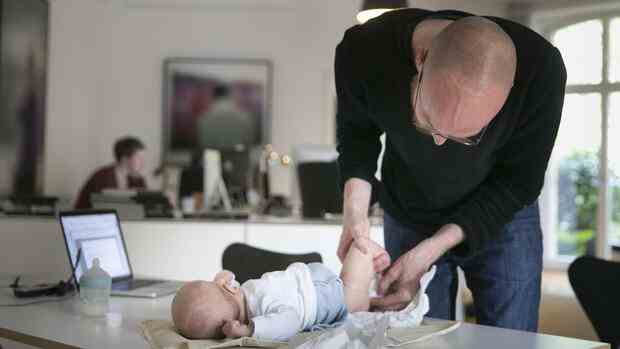

The participation of women in the labor market could be noticeably increased with considerable efforts in institutional child care. However, this increase in employment was primarily accompanied by rising part-time rates. Almost half of the women in Germany work part-time, but only every ninth man – and this even though the participation of women in education is now higher than that of men.

Part-time is crucial

In order to reconcile the demand for labor with the perspectively shrinking supply, it would make sense to at least stabilize the volume of work through longer average working hours. Nevertheless, an increase in weekly working hours is rarely discussed without prejudice, even if there is undoubtedly potential here compared to the EU.

In 2021, workers in Greece worked the longest at 41.3 hours per week, followed by Bulgaria and Poland at a good 40 hours. Only Denmark and the Netherlands worked less than in Germany. The decisive variable is the part-time rate in the respective countries.

Prof. Bert Rürup is President of the Handelsblatt Research Institute (HRI) and Chief Economist of the Handelsblatt. For many years he was a member and chairman of the German Council of Economic Experts and an adviser to several federal and foreign governments. More about his work and his team at research.handelsblatt.com.

It is now anchored in Germany’s constitution that the parties to the collective bargaining agreement agree on wages and working hours. The state’s abstinence in this regard has certainly proved its worth, especially since trade unions and employers’ associations are consistently open to well-founded advice. In view of the worsening labor shortage, it would be advisable to agree on regulations and opening clauses that are as flexible as possible, so that all those employees who want to work more can also work more and thus earn more money.

Politicians would be well advised to see it as a task to increase the financial attractiveness of overtime. An example of this is the tax exemption for Sunday and public holiday surcharges introduced in 1940. The German Reich wanted to create a financial incentive for workers in the armaments sector.

Other special rules for certain forms of overtime would therefore be quite conceivable today. In fact, however, especially in the middle income segment, additional income is heavily burdened in the interplay of progressive income tax and social security contributions. It is not uncommon for only around 40 cents net to remain in the account for every additional euro earned. The incentive to work and earn more is therefore not particularly high, except at night and on weekends.

The unfortunate finding is that in Germany people often only work part-time. The good news is that this finding also harbors an opportunity. With an overall significant increase in employment, in many cases individuals would not even have to work full-time to earn a sufficient family income.

If productivity development continues to be as weak as in the past, the pressure to increase individual working hours should increase of its own accord. Otherwise, income growth in Germany lagged behind that in other countries. The high part-time rate therefore represents a well-stocked reservoir to counteract the increasingly lamented labor shortage.

More: Working 100 percent, earning 80 percent: why part-time work is often self-deception for highly qualified employees