The news sounds scary, but is it actually true? Foreign Minister Annalena Baerbock is inciting the Ukrainians to go to war against Russia. The claim comes from a report recently published in Spain by the Russian foreign media Sputnik.

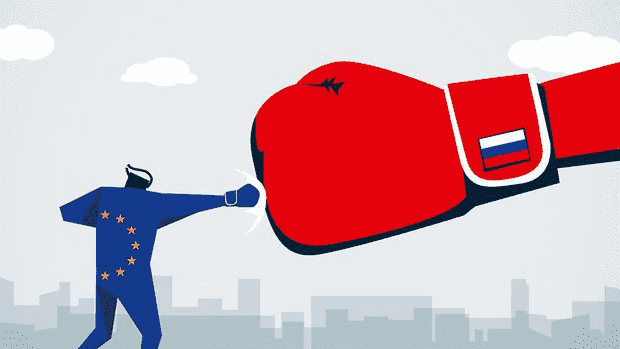

Shortly thereafter, experts from the “East Stratcom Taskforce” in Brussels debunked a “pro-Kremlin disinformation narrative”; the West is accused of “fomenting the conflict in Ukraine”, while Russia is portrayed as “purely defensive”. Many such false reports and their clarification can be found in the “EU vs. Disinfo” database. And there are more and more. Because even in a hybrid war, the truth is the first casualty.

Behind “EU vs. Disinfo” is the “Strategic Communication” unit. It is the European Union’s response to covert information campaigns from Moscow. In 2015, after the annexation of Crimea and the outbreak of war in eastern Ukraine, the so-called Strategic Communications Team East, the task force, began its work – in response to the propaganda with which Putin’s Russia wants to manipulate opinions abroad.

“Bringing light into the darkness” is how Lutz Güllner explains the task of his unit, which he has been in charge of since 2018. The task force has uncovered thousands of cases so far. Influencing that can become a security risk.

Top jobs of the day

Find the best jobs now and

be notified by email.

The Ukraine crisis is making that clear. Since the Russian troop deployment, the disinformation has increased even more. Observers have been warning for days that the Kremlin could be spreading false information to create a pretext for invading Ukraine. Brussels promises Ukraine more help against such hybrid threats.

“The EU has significantly increased its capacity and efforts to identify emerging disinformation and misinformation, analyze threat levels and coordinate appropriate responses,” a Commission spokesman said earlier in the week.

The representatives of the EU Parliament also see it that way. “Current crises show us how important it is to expand our tools to combat disinformation,” says Sabine Verheyen. The fight is a “red-hot and central challenge for the EU,” said the CDU MP.

The Russian state broadcaster RT has not received permission to broadcast on television in Germany.

(Photo: dpa)

In Europe, however, many such dangers have been underestimated. The Kremlin has been using deliberately circulated misinformation as a weapon for years: in the Ukraine conflict, the 2015 refugee crisis, Brexit, the refugee crisis on the border with Belarus, and now the escalating Ukraine crisis. It’s always about sowing mistrust in Europe – in order to profit from it politically. According to a study from the previous year, Germany is the number one destination. Although other countries are increasingly using misleading claims, Russia is seen as a key player.

The EU tries to give the impression that it is doing a lot, says Špalková, “but it is definitely not enough”. Alberto-Horst Neidhardt from the independent Brussels think tank European Policy Center agrees that “more preventive measures are needed”.

There is also criticism of the task force’s approach. A few months ago, the “Guardian” reported on an intervention by EU foreign policy chief Josep Borrell in an analysis of Chinese narratives. A weakened report was published – apparently under pressure from Beijing. A former Taskforce employee recalls: For a long time, many in the EU had not believed in external influence, and the support for the Taskforce’s policy was correspondingly “hesitant”.

That has changed. For more than a year, a special committee of the EU Parliament has been developing measures to combat hybrid threats. “We have to do something against disinformation,” demands MEP Alexandra Geese (Greens). “It needs clear rules.”

>>Read more about fake news in the EU: EU sees Germany as the main target of Russian disinformation

The EU, says CDU politician Verheyen, must protect media freedom and at the same time ensure that it is not “exploited by those who spread disinformation”. Political control mechanisms are needed, including the withdrawal of licenses from media that spread targeted misinformation – in order to protect freedom within the EU from hybrid warfare.

The 65-page report by the parliamentarians, which is to be approved by the plenum in March, lists suggestions for improvement. The EU needs a coordinated strategy, it says, and many measures need to be further developed, including the work of the task force.

Demand for additional resources

They need more money and staff, more skills and more exchange within the Union. Former employees, EU officials and independent observers agree. Many would also like to see the task force under the umbrella of the Commission rather than under the leadership of the EEAS. Both institutions share responsibilities in disinformation and other hybrid warfare strategies, including cyberattacks, which many see as weakening their effectiveness.

However, anyone who deals with the fight against disinformation in Brussels also knows that not all problems can be solved with one instrument anyway. That’s why the EU wants to bring up more artillery.

Great hopes are pinned on the so-called Digital Services Act (DSA). The future EU regulation on digital services is intended to put an end to the “wild west that the digital world has become”, as it is called in Brussels, and is considered one of the most important projects in this legislative period.

It’s about more rights and transparency towards online platforms, and action should be taken against content that is harmful but “not necessarily illegal” – such as fake news. The law is scheduled to come into force in 2023.

The MEP has called for a binding law to combat disinformation.

(Photo: imago images/Future Image)

With the voluntary code, the responsibility has so far been with the platforms themselves, complains Green MP Geese. “Because that didn’t work, there is now a law.” Social networks are to be obliged to disclose how their algorithms work, which decide which messages or videos are displayed to users.

“In order to take action against disinformation, you have to know and understand the business model and the algorithms,” explains Geese. It has been proven that polarizing content and false news spread faster than factual information.

The parliamentarian emphasizes that it is about correcting these forms of distribution, not about banning content. The aim is to reduce “the artificially increased reach of disinformation today, so that more serious messages are more visible again”.

However, the voluntary code is to remain in place and will be revised by March. Companies should do more than they actually have to do legally in the future. Companies shouldn’t be left to decide whether or not to take action, says Alexandre Alaphilippe, founder and director of the Brussels-based NGO Disinfo Lab. He believes that the EU is moving in the right direction with the DSA, but it is still not enough.

Especially since the dangers continue to increase, as Taskforce boss Güllner warns. Dozens of countries have built complex infrastructures to spread disinformation, Güllner speaks of an “industrial scale”. Sometimes it’s about geopolitics, sometimes about a country’s reputation, sometimes economic interests are in the foreground.

Resistance to this, everyone in the EU agrees, can only succeed together: politicians, platforms, researchers, journalists and fact-checkers must be involved. Society’s media skills must be strengthened.

Some think even further and bring sanctions into play. So far, those responsible for manipulating news have been able to assume “that their destabilization campaigns against the EU will have no consequences,” according to the report of the parliamentary special committee. But actors should “have to bear the consequences of their decisions”.

Legal steps are being considered, according to diplomatic circles. However, it took two years for the EU to create sanctions in response to cyber attacks. It remains to be seen whether the Ukraine crisis will lead to faster reactions – so that Europe can better defend itself against disinformation, as in the case of Baerbock’s alleged hate speech.

The research was supported by the Goethe Institute in Brussels.

This text first appeared in the Tagesspiegel

More on this: German economy fears the Russia crash