Each EU country should agree a tailor-made multi-year debt reduction plan with the EU Commission.

(Photo: IMAGO/NurPhoto)

Brussels After a delay of months, the EU Commission presented its proposal for the reform of the European Stability and Growth Pact on Wednesday. According to Handelsblatt information, the Brussels authority wants to give the member states more flexibility in reducing debt. At the same time, the rules should become simpler and more binding.

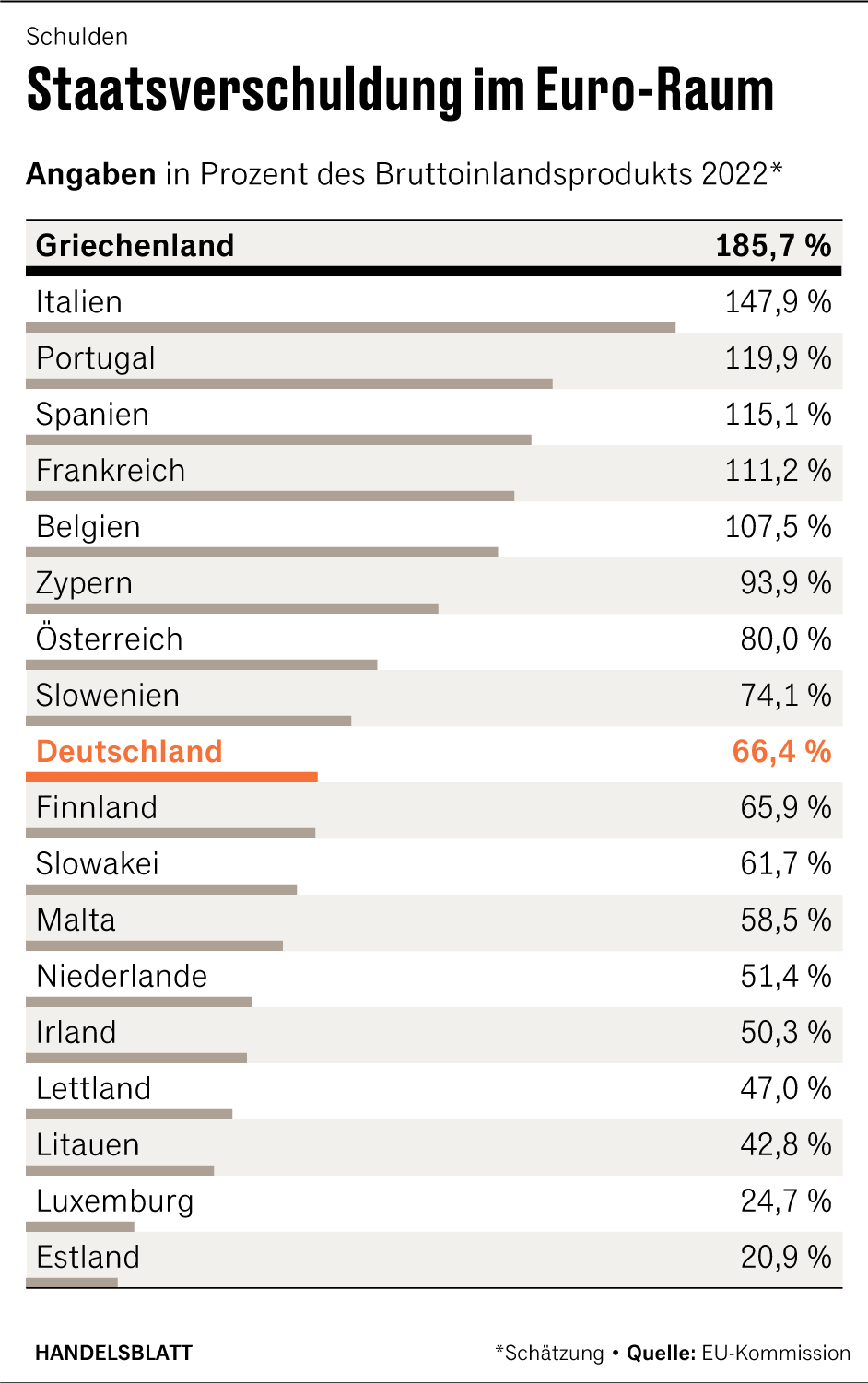

The most important innovation is the abolition of the one-twentieth rule. So far, this stipulates that over-indebted countries must reduce their total debt below the Maastricht upper limit of 60 percent of gross domestic product within 20 years. In view of the sometimes three-digit debt ratios after the corona pandemic, this goal is considered unattainable for a number of European countries.

Instead, in future each country should agree a tailor-made, multi-year debt reduction plan with the Commission. Its requirements vary in severity, depending on how heavily indebted the country is.

The states are divided into three categories: In the first group are the high-risk countries with a national debt of more than 90 percent of the gross domestic product. These currently include Greece, Italy, Portugal, Spain, France, Belgium and Cyprus.

Top jobs of the day

Find the best jobs now and

be notified by email.

In the second group are the countries whose public debt is between 60 and 90 percent. This includes, for example, Germany (66 percent). Finally, the third brings together those who remain below the Maastricht ceiling and are therefore not considered to be over-indebted.

>> Also read: EU debt rules: 90 is the new 60 – Brussels capitulates to the sad reality

All over-indebted states must achieve a sustainable debt reduction path within four years. The high-risk countries have to reduce their debt faster than medium-risk countries.

EU Council must approve any debt reduction plan

The annual new debt may not amount to more than three percent of the gross domestic product. In the event of violations, an excessive deficit procedure is automatically initiated against high-risk countries, which places a country under the heightened supervision of the Commission.

Upon request, the adjustment period can be extended to seven years if the government can demonstrate concrete structural reforms or investments that contribute to long-term debt sustainability. Any national debt reduction plan must be approved by a qualified majority in the EU Council.

The Commission’s proposal is not yet a draft law, but initially only a communication. The 27 finance ministers want to discuss the details at their next meeting in December. A legal text is expected in the spring at the earliest.

Because the reform is controversial. The federal government also still has objections to the commission plan. In Christian Lindner’s (FDP) Ministry of Finance, the main fear is that the debt reduction plans will not be ambitious enough if they are negotiated bilaterally between the EU Commission and national governments.

Doubts about the schedule

The Vice-President of the European Parliament, Nicola Beer (FDP), warns that such a practice would lead to a “stability policy dead end”. Each new government could then renegotiate the rules. “There would be no hint of reliability.”

Experts also see the problem. “We do need some discretion, because you can’t do everything with rules. But the question is, who exercises it?” says Jeromin Zettelmeyer, director of the Bruegel Institute in Brussels. “If the Commission and the Member State agree on the debt reduction plan bilaterally, it will be politically difficult.”

The economist therefore proposes that an independent national institution must also approve the plan in each country. In addition, high-risk countries would have to be required to achieve a balanced budget, the so-called black zero, within a few years.

The Vice President of the European Parliament, Nicola Beer (FDP), has concerns about the planned EU debt rules.

(Photo: ddp/Panama Pictures)

There are also doubts about the schedule. Actually, the Stability Pact should come into force again in 2024 – and then in a refreshed form. The debt rules have been suspended since the beginning of the pandemic; most recently, the exemption was extended until the end of 2023 due to the war in Ukraine.

In Brussels, however, it is considered unlikely that the legal acts can be changed so quickly. According to EU circles, the reform is technically difficult and politically controversial. “That may take a few years.”

The Liberal Beer is also skeptical: the mere fact that the EU Commission has not yet been able to present a draft law shows that the votes on this are delicate. “The targeted timeframe seems very unrealistic to me.”

More: The federal government makes twice as much debt as planned – Lindner still wants to comply with the debt brake