According to the Commission’s plan, every government will in future agree a tailor-made, multi-year debt reduction plan with the Brussels authorities.

(Photo: ddp/abaca press)

Brussels The EU Commission wants to give the member states more time to reduce their debt. According to information from EU circles in the Handelsblatt, every government should in future agree a tailor-made, multi-year debt reduction plan with the Brussels authorities. The idea is to simplify debt rules and tighten controls.

The Commission will probably only present its proposal for the reform of the Stability and Growth Pact in November. So far, she had aimed for the end of October. There is now an agreement between the lead commissioners Valdis Dombrovskis and Paolo Gentiloni, it said. But the authority does not want to be accused of having acted rashly on the last stage. The debate on the debt pact has now lasted two years. From the Commission’s point of view, a few more weeks is irrelevant.

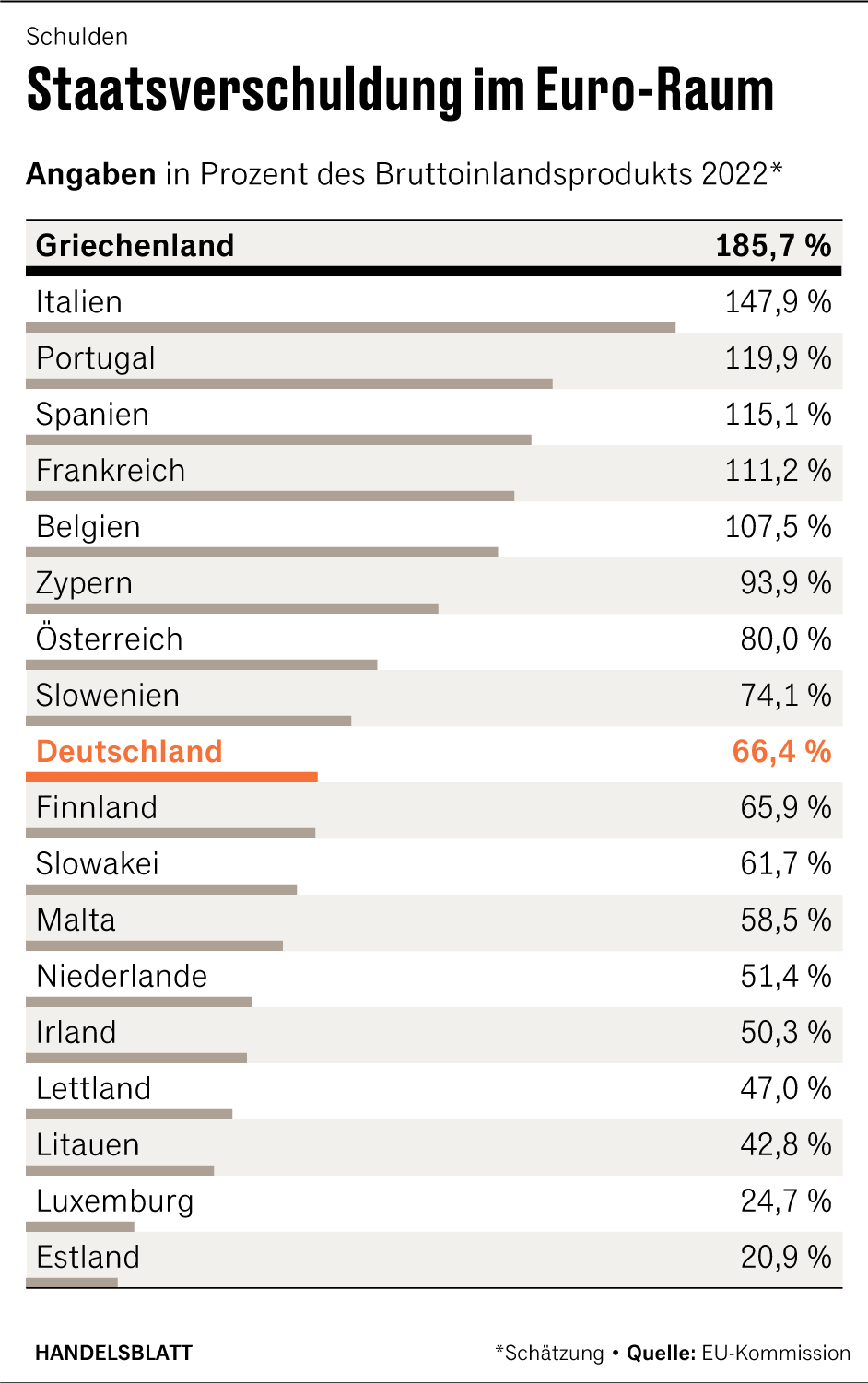

The core of the reform is the abolition of the so-called one-twentieth rule. This stipulates that states must reduce their debts to the upper limit of 60 percent of gross domestic product within 20 years. Since the Corona pandemic, this requirement from the Maastricht Treaty has been considered unattainable for several countries because debt has risen so much. Greece’s debt ratio, for example, is almost 186 percent, Italy’s 148 percent.

Maastricht upper limits should remain in place

The Commission is therefore proposing a new rule: “high-risk countries” (countries with a debt ratio of well over 90 percent) should in future be given four years to get on a sustainable debt path towards the 90 percent milestone. Once they reach 90 percent, they are considered medium-risk countries and can slow further deleveraging towards 60 percent somewhat.

Top jobs of the day

Find the best jobs now and

be notified by email.

>> Also read here: These are the poorest countries in the EU

The Maastricht upper limits of 60 percent for government debt and three percent for annual new borrowing are to remain in place. Even if they currently seem unattainable for some states, they are seen as an important commitment to budgetary discipline, especially by the “hawks” among the member states.

According to the reform proposal, the debt reduction plans are to be negotiated bilaterally between the Commission and the national government. The states commit themselves to certain reforms, such as the pension system. The model is the Corona reconstruction fund, in which the Commission and member states have agreed on reform steps and investments. This approach is intended to allow more flexibility for investments in green transformation or defense than the rigid one-twentieth rule.

>> Also read here: “There’s going to be a big debate” – Lindner paves the way for the European debt debate

A debt reduction plan will only be approved if the Commission concludes that the debt burden is sustainable over the long term. She wants to use the instrument of debt sustainability analysis, which is also used by the International Monetary Fund (IMF). The development of the debt level is calculated assuming certain growth, inflation and interest rates. Each individual plan then has to be approved by the Council of 27 member states.

At the same time, control is to be tightened: If a government deviates from its agreed debt reduction path, the Commission is to start deficit procedures and place the country under stricter surveillance. A government can also negotiate with the Commission to extend the four-year period by up to three years. But there must be good reasons for this.

The stability pact has been suspended since the beginning of the corona pandemic in spring 2020. It is to come into force again in 2024, then in a reformed form. In view of the sharp increase in debt in the EU, there is agreement that the previous rules need to be revised. The plan has met with approval in the European Parliament. “We need more flexibility when it comes to debt reduction and green investments,” says Rasmus Andresen, spokesman for the German Green Party.

More: Is the euro crisis looming after the energy crisis?