They come by bus, train, car and foot, 100,000 to 200,000 or more every day, enduring often freezing temperatures and waits of up to 60 hours to cross the border. Ukrainians fleeing the chaos and carnage of the Russian invasion are flooding into neighboring Poland, Hungary, Romania, Moldova and Slovakia, some looking to stay and others on their way to more distant destinations, in numbers not seen in decades. By the end of the first week of the war, more than 1 million residents of Ukraine had left their homes looking for safe haven outside its borders, and the United Nations estimates their numbers will likely top 4 million in coming months.

“At this rate, the situation looks set to become Europe’s largest refugee crisis this century,” says U.N. refugee agency spokesperson Shabia Mantoo.

U.N. High Commissioner for Refugees Filippo Grandi concurs, telling a recent emergency session of the U.N. Security Council: “I have worked in refugee crises for almost 40 years and I have rarely seen such an incredibly fast-rising exodus of people—the largest, surely, within Europe, since the Balkan wars.”

Ethan Swope/Bloomberg/Getty

For now at least, the refugees have mostly been warmly welcomed by the countries they’ve entered, both by the government and ordinary citizens, with what Grandi calls “extraordinary acts of humanity and kindness.” The European Union has stated that its member nations are open and eager to host Ukrainians looking to escape the violence at home, and is poised to invoke, for the first time in its history, a directive that will allow the refugees to stay and work in EU countries for up to three years.

“This is a situation where we could have millions of people on our territory and we need to make sure that they have the proper protection and the proper rights,” Ylva Johansson, the European Commissioner for Home Affairs, told Euronews. “Most Ukrainians coming now, they are coming with passports that give them visa-free entry for 90 days. But we have to prepare for day 91.”

Thierry Monasse/Getty

Still, with a sudden influx of refugees of this magnitude, strain is inevitable, and some signs of it are already evident. For one, reports are growing about unfair treatment of refugees of color, many of whom are facing pushback and discrimination compared to white Ukrainians en route to and at border crossings. Meanwhile, the immediate humanitarian challenges are overwhelming, as host nations try to figure out how to provide healthcare, food, housing, education and security for hundreds of thousands, and ultimately millions, of displaced people for an unknown period of time. Slovakia, which saw more than 90,000 Ukrainians enter the country in the first week of the war, has already declared a state of emergency.

“We know that we are not even scratching the surface to meet the needs of Ukrainians,” Grandi said in a statement to the U.N. Security Council, speaking both of the refugees and those still in the country, many of whom have relocated to avoid attacks by the Russian military. “The situation is moving so quickly, and the levels of risk are so high by now, that it is impossible for humanitarians to distribute systematically the aid, the help that Ukrainians desperately need.”

Michele Tantussi/Getty

Longer term, there are concerns too, particularly that such a massive movement of people, unseen in Europe since World War II, could pose serious economic and political problems in host countries, putting a strain on jobs and resources and prompting a backlash against the newcomers. “We should not be naive,” Johansson told Euronews. “Millions and millions of Ukrainian refugees will of course cause a challenge to our societies.”

As U.S. Ambassador to the United Nations Linda Thomas-Greenfield warned, in discussing the looming refugee crisis before the U.N. General Assembly: “The tidal waves of suffering this war will cause are unthinkable.”

View From the Border

The mass exodus from Ukraine—roughly 10 percent of the population is expected to leave the country in coming weeks and months—is possible because of an agreement with the European Union that allows Ukrainians visa-free entry to EU member nations and stays of up to three months. In the current situation, though, that theoretical ease of movement has led to a huge bottleneck at border crossings.

People fleeing in cars face hours-long traffic jams with lines of cars sometimes stretching for dozens of miles. Bus and rail stations are overflowing. As they near the border, many Ukrainians end up abandoning their mode of transport and trudge along on foot—often, according to an AP report, with a child on one arm and suitcases on the other.

Andrei Pungovschi/Bloomberg/Getty

Some of those fleeing tell harrowing tales of escape. “The situation was very terrible,” Priscillia Vawa Zira, a Nigerian medical student who left Kharkiv for Hungary, told AP. “You had to run because [there were] explosions here and there every minute, run to the bunker.”

Natalia Pivniuk, who left Lviv for nearby Poland, described people in crowds shoving each other to board trains out of Ukraine. She told AP the experience was “very scary, and dangerous physically and dangerous mentally,” adding, “People are traumatized.”

Long delays are common once at the border. Ukrainians crossing into Poland, which has received the largest number of refugees by far, face waits of up to 60 hours amid freezing temperatures, according to the UNHCR; in Moldova, it’s as long as 24 hours and 20 hours in Romania. Citizens of other countries who were living in Ukraine have faced even greater difficulties and longer delays, if they’re able to cross at all.

The majority of those making the trek are women, children and older adults since most men between the ages of 18 and 60 are prohibited from leaving Ukraine under recently-declared martial law. U.S. independent journalist Manny Marotta, who arrived in Ukraine in mid-February to cover the conflict but walked for 20 hours to cross to safety in Poland after the war broke out, says Ukrainian army patrols at the border separated men of conscription age from their families, seeking to send them back home to help defend the country. “The kids didn’t understand why their dads were being taken away, they tried to protest [but] they were taken away,” he says. “A man was arguing about staying with his wife and the soldier turned to the crowd and said, ‘look at this coward, he’s not fighting for Ukraine’ and the crowd booed him and [then] he went with the soldier.”

Diego Herrera/Getty

Makeshift facilities to process the newcomers have sprung up along the border. Tents have been erected in some places to provide medical aid and process asylum papers, along with temporary beds so Ukrainians who have been traveling for long hours or days can rest. Troops have also been sent to border checkpoints with instructions to provide assistance to the refugees, according to Reuters.

On top of the efforts of national authorities and humanitarian agencies, local organizations and individual volunteers have also come out in force to support the new arrivals. Near the reception centers in Poland, collection points have popped up to receive items being donated, according to reports from ReliefWeb, a humanitarian information portal. In just a few days, the facilities have been filled with food, water, clothes, sleeping bags, shoes, blankets, diapers and sanitary products for people who are arriving with only what they can carry.

Beata Zawrzel/Getty

Just beyond the border point in Dorohusk in Poland, locals are offering free rides to arrivals with family in Poland, holding up cardboard signs asking, “Where do you want to go?” in Ukrainian. Near the country’s border crossing in Medyka, a nun hands out battery packs and cell phone charging cables to help refugees stay connected. Other volunteers bring cookies.

Some private companies are also stepping up. Airbnb announced it will provide temporary housing at no cost for up to 100,000 Ukrainians in countries with a mass influx of refugees. Many train operators are offering free travel for Ukrainian refugees. Meanwhile, Wizz Air, a Hungarian airline, is offering free passage out of Ukraine’s border countries, committing to provide 100,000 free seats on flights leaving Poland, Slovakia, Hungary and Romania this month. Khazickstan carrier Air Astana also said that it has “repatriated” almost 300 Kazakh citizens from Ukraine at no charge, according to the aviation news outlet Simple Flying. And Ryanair, an Irish airline, has been flying in humanitarian cargo to Polish airports “for the first time in 30 years,” the airline’s chief executive, Michael O’Leary told the Guardian.

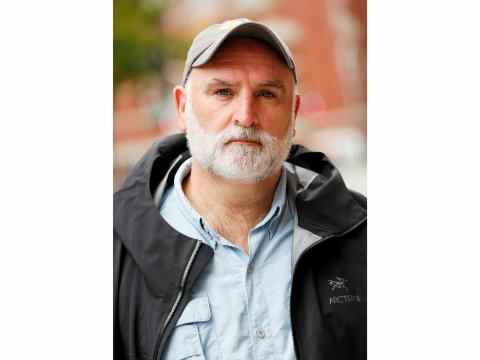

And in an effort documented on his Twitter page, Chef José Andrés, who won a $100 million award for his humanitarian efforts last year from Amazon founder Jeff Bezos, is helping to feed refugees at the Ukraine-Poland border through his nonprofit World Central Kitchen (offerings include soup, chicken stew, hot tea and apple pie). In a recent tweet praising all of the volunteer efforts he and his team have encountered at the border, he said: “Firefighters, school teachers, students doing whatever it takes to bring comfort to refugees feeding etc all the time non stop! 24/7 an Army of empathy and love!”

Paul Morigi/Getty

Past As Prologue?

While sympathies for Ukrainians trying to escape Russian bombs and tanks currently run high, only time will tell how long these attitudes last. Serena Parekh, an expert on the ethics surrounding displacement and refugees with Northeastern University, warns that if dialogue around Ukraine’s plight is not maintained, the situation could devolve into a scenario that would fit neatly into Russian President Vladimir Putin’s political playbook.

“A refugee crisis could play into Putin’s strategy if his goal is to destabilize Western democracies and cause right-wing backlash and the rise of authoritarian leaders,” Parekh tells Newsweek. “We saw this [phenomenon] after the 2015 refugee crisis in Europe.”

At that time, Europe experienced the largest refugee wave it had seen since World War II, as roughly 1.3 million people, mostly from Syria, fled their war-torn homelands for the safety of Europe. Parekh noted that early on, as the public was confronted with images of the refugees’ plight, sympathy and the desire to provide aid ran high.

In time, though, that attitude changed. As news of the initial devastation facing the Syrian people subsided, members of the European public began to see the refugees as a problem. Parekh said right-wing leaders promoted narratives of the Syrian arrivals being an economic burden to European nations and amplified the religious and cultural differences that set them apart from many EU citizens.

Spencer Platt/Getty

While Ukrainians have things in common with Europeans that Syrians largely do not, namely skin color and religion, Parekh said there is still room for divisiveness given certain perceptions among Western Europeans that Eastern Europeans are poor, take resources and do not share their cultural values.

The amplifying of those themes within European politics in 2015, as Parekh and other experts note, spurred a rise in right-wing sentiment across Europe. If the same thing happens again, Parekh says, it could work to Putin’s advantage.

“Right-wing governments that have emerged in the last eight years or so have tended to have authoritarian tendencies, moving away from the rule of law, principles of human rights and internationally recognized treaties,” Parekh tells Newsweek. “Undermining the principles of liberal democracy, such as rule of law, democratic elections, international law, puts less pressure on Putin to be democratic and to respect the rule of law.”

Some experts, including RAND Corporation adjunct senior fellow Charles Ries and senior policy researcher Shelly Culberston, now warn that the Ukrainian refugee situation could impact European politics “as much or more than” the 2015 crisis.

“In the event of much larger movements of Ukrainians this year, the political impacts could be similar and bolster right-wing and nationalist movements,” Ries and Culberston said in an OpEd for Newsweek published the week before Russia invaded. “Any backlash to the refugees in communities experiencing migrant flows could further divide NATO members—an effect that would be welcomed in Russia, and perhaps enhanced by disinformation efforts.”

A Different Perspective

One group of refugees whose experiences sometimes diverge from the warm welcome many Ukrainians get upon crossing the border: non-Ukrainian people who lived, worked or studied in Ukraine but aren’t citizens. Benjamin Ward, deputy director of Europe and Central Asia for Human Rights Watch, says that non-Ukrainian nationals, including people from Afghanistan and India, have weaker legal positions at European borders and might not be received as openly and kindly as Ukrainians who mostly share similar cultures and religion with Europeans.

Some Black immigrants who were living in Ukraine and attempted to escape to safety once war broke out have felt this divergence sharply. African students trapped in the country have taken to social media to document the hurdles and hostility they have faced while trying to flee, using the hashtag #AfricansInUkraine on Twitter.

Several videos have gone viral on social media appearing to show Black people being denied access to trains, including one that showed Ukrainian forces apparently pushing a Black girl off a train but allowing a white girl aboard. Other videos captured ugly incidents at border crossings and African immigrants left stranded, including one clip that captured a Black woman feeding her two-month-old baby in freezing temperatures.

Akos Stiller/Bloomberg/Getty

Alexander Somto Orah, a Nigerian student who’d been attending a university in Kyiv, says he experienced “segregation and discrimination” from Ukrainian law enforcement officers as he tried to cross the border into Poland. He has now made it to Warsaw but shared videos on Twitter that he says showed officers threatening to shoot African students trying to cross the border. Barricades were set up 30 minutes away from the Medyka border, he says, separating refugees by color. “They kept whites on [one] side and non-whites on the other, allowed whites to cross [but made] us sleep there for days,” he tells Newsweek. “We started protesting and the police started threatening to shoot us. After a while we broke through the barricades.”

Another student, Gabriel, told the BBC that border guards were “just so heartless…they treated us like animals.”

Korrine Sky, a student doctor who made it to Ukraine’s border with Romania, shared a video on Twitter showing a man circling the vehicle she was traveling in. “We have reached the actual border experiencing some threats of violence from some local Ukrainians who don’t believe we should enter,” she wrote.

In an Instagram livestream on Sunday, Sky said, “There’s been a lot of segregation and racism from the people who’ve managed to actually get to the passport control. It seems there is a hierarchy of Ukrainians first, Indians second, Africans last.”

Ukraine is home to tens of thousands of African students studying medicine, engineering and other subjects at affordable prices.

On Twitter, activist Shaun King reported that it wasn’t only Black people experiencing discrimination at border crossings. “It’s not just Africans having trouble crossing, but ALL immigrants of color including Indians, Latinos, Arabs,” King wrote on Twitter on Sunday, citing conversations with people across Ukraine. “European immigrants crossing easily.”

In another tweet, King wrote: “To be clear, government officials in Poland, Bulgaria, Hungary are SAYING they will welcome all people crossing over from Ukraine, but those policy statements still have not been implemented at those same borders. Each border, today, is still having ugly incidents of racism.”

What Would Help

Experts note that, just one week into the mass flight of Ukrainians from their country, it’s too soon to make pronouncements about the long-term economic and political impact or to judge the effectiveness of efforts to assist the refugees—or even, perhaps, to deem the situation a crisis.

Alejandro Martinez Velez/Getty

John Borneman, an anthropology professor at Princeton University who has studied how Syrian refugees in Germany adapted to their new environment in 2015, is among those who believe the prevailing description of the situation is unduly alarmist. “This is not a crisis, and if so, only for the Ukrainians fleeing,” he tells Newsweek. “It is certainly not [a crisis] for the receiving nations where the incorporation of refugees will be somewhat distributed.”

Borneman points out that the initial characterization of the Syrian refugee situation as a crisis faded in time, contradicting pundits’ predictions. But his view on Ukraine makes him something of a lone wolf currently and deep concerns prevail about the ability of European countries to absorb, house, feed, provide medical treatment and supplies and, perhaps in time, jobs to the new arrivals.

Figuring that out as quickly as possible, experts agree, is critical to mitigating possible tensions in Europe and getting the necessary assistance to the Ukrainians currently seeking asylum and millions expected to join soon. A report by ReliefWeb notes that it is important for EU policymakers to show they can handle the refugee situation by coming up with a plan that includes a system for managing and controlling arrivals and avoiding “chaotic border scenes.” The report said: “It is these scenes of chaos and poor management that have fueled an ever-growing list of reactive and restrictive stances on humanitarian protection and migration across the bloc in the past months.”

RAND’s Ries and Culberston suggest one step that EU and NATO members might take to help manage the situation is to enact national plans that are already in place for natural disasters such as flooding. An example might be Slovakia’s recent declaration of a national emergency, which facilitated new spending of $14.5 million on border infrastructure and to complete asylum facilities, according to The Washington Post.

Also helpful: the EU’s plan to activate a directive, in place but never used before, to help member states collectively manage and share the applications of all the Ukrainian nationals who are expected to enter the bloc. The plan would also grant Ukrainians permanent residence and access to housing, work, health care and education for at least one year; if the conflict continues and it is deemed not safe for refugees to return to Ukraine, they could seek asylum for another two years.

Alejandro Martinez Velez/Getty

Refugees who don’t have Ukrainian citizenship or the right to permanently reside in the EU, such as international students, however, will not be covered under the law. Instead, the EU will help people return to their home countries.

To assist internal aid organizations, raising additional funds to cover the high and rising costs of humanitarian assistance is also critical. Toward this end, the UNHRC has asked for $1.7 billion in relief aid for Ukraine, with $1.1 billion earmarked for help within the country and the rest to support Ukrainian refugees in neighboring countries. Said UNHRC’s Grandi, “While we have seen tremendous solidarity and hospitality from neighboring countries in receiving refugees, including from local communities and private citizens, much more support will be needed to assist and protect new arrivals.”

Efforts to help the Ukrainian newcomers assimilate over the longer term will also be key. While returning home is typically the goal of people seeking temporary asylum, a recent RAND study found that 10 years after a conflict’s end, fewer than a third of refugees had actually returned to their country of origin.

That suggests that millions of Ukrainian refugees are likely to end up being permanent residents of their new host countries, whether that’s their current intent or not. If so, learning to live together, rather than in limbo, may turn out to be the most important challenge to tackle for both refugees and the European countries providing refuge.

Additional reporting by Jon Jackson, Emma Mayer, Alex J. Rouhandeh, Zoe Strozewski and Katie Wermus.