Silverstring Media makes challenging games, but not in the way that some players might expect. The studio creates plenty of abstract and thematically complex titles, alongside its work fine-tuning gems like Crypt of the Necrodancer. One of Silverstring’s chief successes was Glitchhikers, an experimental work released in 2014, and the project is now receiving a revisit in the form of Glitchhikers: The Spaces Between.

Rather than a video game sequel of Glitchhikers, The Spaces Between is a large expansion on the original work. The theme is similar, focusing on the introspective moments that someone finds during night travel, but whereas the first Glitchhikers was purely about a nighttime drive, The Spaces Between covers plenty of other journey types. Whether a late night walk or an overnight train, Glitchhikers: The Spaces Between gives everyone a chance to connect with the weird.

Ahead of the game’s launch, Studio Director Lucas J.W. Johnson and Creative Director Claris Cyarron chatted with Screen Rant about Glitchhikers: The Spaces Between, and the journey that Silverstring Media took over its development.

Glitchhikers is a fascinating project. It was originally a short form experience; what made you want to return to expand on that original design? Was it always part of the plan to build more elements into it or was it something that came to you later down the line?

Lucas J.W. Johnson, Studio Director: When we first made Glitchhikers back in 2014, which is now redubbed Glitchhikers: First Drive, we knew there was more we could do with it. Very soon after releasing it and talking to people, we really started to see the potential for more. The premise of First Drive is the so-called ‘universal experience’ of driving alone on a highway alone at night, and 80% of the people we pitched the game to said “I get that. That’s what the game’s about, that’s really cool, I want to check it out.” The other 20% would say “I don’t drive – I don’t know that experience.” Of course! Not everyone drives, and in particular car culture is such a North American thing. If you talk to Europeans they wouldn’t have that necessarily, but they would know the train journey. We took it from there. There was so much more to it that we could explore.

At the core of it, the idea of Glitchhikers is this universal journey liminal space. It’s about the journey, and everything we do is meant to make it feel like that particular kind of journey to get you into that headspace – it’s more about the headspace than the journey itself. In the drive, you don’t have free control of the car; you’re not driving off the highway because it’s not a driving game in that way. It’s about the headspace of this late night experience.

We quickly saw that there was a lot more we could do with it, and Glitchhikers: First Drive had such an impact on a lot of people. Years later we would see people on Twitter say “top ten games of all time for me – Glitchhikers among them” and holy cow that’s amazing! So, we knew it had some legs and over the last several years we kept saying that we could revisit Glitchhikers as there was a lot more we could do.

Claris Cyarron, Creative Director: We were fortunate to have this amazing team that we were able to bring back and expand for Spaces Between. Early on in our career when Lucas and I were just getting started working in games, to have a game that made this nice big splash relative to its size really led us to ask over time why it worked so well. The thing that was really fruitful and fun as designers was that there kept being more answers.

Partially it was discovering ways that we could get through to that liminal, dreamy space in different ways, using different calm and mundane spaces that people have experiences with. But it was also the ways in which people’s experiences to games change across time. From 2014 to now, this kind of thread went from “I’m not really sure games are supposed to be this kind of weird mechanics-light type experiences. I don’t if you can really play a game where the game is between you and yourself, does that count?” Whereas now, of course that counts! That’s super fun and really valuable.

So, there was this sense of seeing other people move towards that as well, and seeing the brilliant things that they were doing. That inspired us too. I think there was always this passion for returning here if we had the chance. Then, of course, the stars aligned, and it’s been a fun journey to work on this and try to fit as many kinds of experiences and cast out as wide a net as possible for people.

Glitchhikers really encapsulates a meditative feel. Video games have often been a fantastic place to have that meditative experience – you have games like Proteus and Sunlight, which are specifically framed around that kind of journey, as well as narrative-driven experiences like Kentucky Route Zero.

There are also games that are a lot more violent and a lot more horrifying at times, like Bethesda’s Fallout games, where there’s something really zen-like about progressing across the wasteland, even when you’re surrounded by horrifying people and creatures. But, there’s something great about taking in the scenery and listening to the score. Why do you feel that video games make for such a strong medium for that kind of meditative experience? What is it about them that brings you to that space as developers and brings players to that space too?

Claris Cyarron: That’s totally speaking my language! Fallout: New Vegas, Dark Souls – I love those types of games and I find them very relaxing and meditative. Partly I think it’s that way in which they bridge that gap between you and your body and the game and your digital body; it’s a challenge and it has a lot of the hallmarks of the ways we blur the divide between yourself and any kind of prosthetic device. Once you start to get that connection, and are able to make progress, there’s this feedback loop and you start to feel more and more in command of your body. In dangerous situations there’s a sense of being able to move through those spaces unimpeded by the world, which gives you a sense of mastery and clarity, but it’s also that much more raw, mechanical sense of “I am pushing back on the world and the world is responding to me.” You have that tight push and pull.

Ultimately, that’s one of the things that Glitchhikers: First Drive didn’t have. The first journey that we had was very light on mechanics, and most of those mechanics were narratively and metaphorically resonant, but not very tactile or visceral. I don’t think anyone would call First Drive visceral! But one of the things we really liked doing with the airport mode was to have a lot more mechanical feedback, where you are surfing and skating around this airport terminal, bouncing off things. You can fly, and you have speed pickups – there’s no points, you can’t fail, and it’s never going to be a dexterity challenge like Dark Souls is, but it leans into that.

Video games do that really well, even when they’re not trying to be chill or narrative, so we wanted to capture that. And that’s a really essential part of the magic of games. It isn’t just holding this magic circle. It isn’t just holding space for this narrative. It isn’t just the transformative qualities of moving and integrating into another world and existing there. And it isn’t just pairing that with all of this thematically-laden stuff about travel and the way that travel can be this metaphor for so many things. It’s also about having this push and pull between you and this digital environment. It’s seeing how you react in each different mode, the way you move through the world, the controls you have, the way you react with people, and the way you control the music.

Even though some modes like the drive are very light on interactions, we still took a lot of thought and a lot of time when we brought in each of these modes. What’s the train like, and what’s the unique aspect of that? Being able to move through space while still moving in the same direction with everybody else. You have free agency to pick your seat and move around, but you’re also tied in this place where you’re not really making choices.

Not only were we trying to say “Hey! You might not have an experience with a car but you might have an experience with a red-eye flight”, but we are also giving people experiences they’ve had in other games too. You may not like the slower quality of Glitchhikers: First Drive very much – that might be more of a rarity for you to be in that mood – but if you like games like Dark Souls and want something lighter, kinder, that’s not going to kill you and sour your mood, then you can bounce around in our airport terminal and get that frenetic feel, but still with that Glitchhikers promise of a space that’s safer for you.

One thing that I’ve noticed with Glitchhikers is that the journeys mainly have a hint of nature to them. It might be seeing the forests from the car window or train window, or walking in the park. Did you feel that the connection to nature was useful for the meditative experience? Was it a conscious decision to make sure there was that natural element even in an abstract, more digital world?

Lucas J.W. Johnson: I think a big part of Glitchhikers ultimately comes down to the conversations that you have with the characters that you meet. The thing that we always go back when thinking about what kinds of conversations we want to talk about is the ‘cosmic sublime’. So much of the cosmic sublime is looking up at the stars, at space, and that cosmic element of the natural world in general. What is the universe that we exist in? What is our existence like? It’s all these kind of questions that your mind goes to late at night when you’re not really thinking about anything in particular.

So, the natural world is something that kept coming up in a lot of conversations in a lot of different ways, whether it’s “here’s some cool facts about caves” because caves are cool, or “what is the nature of life and death and decomposition and survival in the face of climate change.” I think that was a constant touchpoint thematically that definitely comes through in the visuals. Of course, another part of it is that when you’re driving along the highway, it’s such a big part of the scenery. It’s about being able to watch those mountains go by, and have that part of the experience as well.

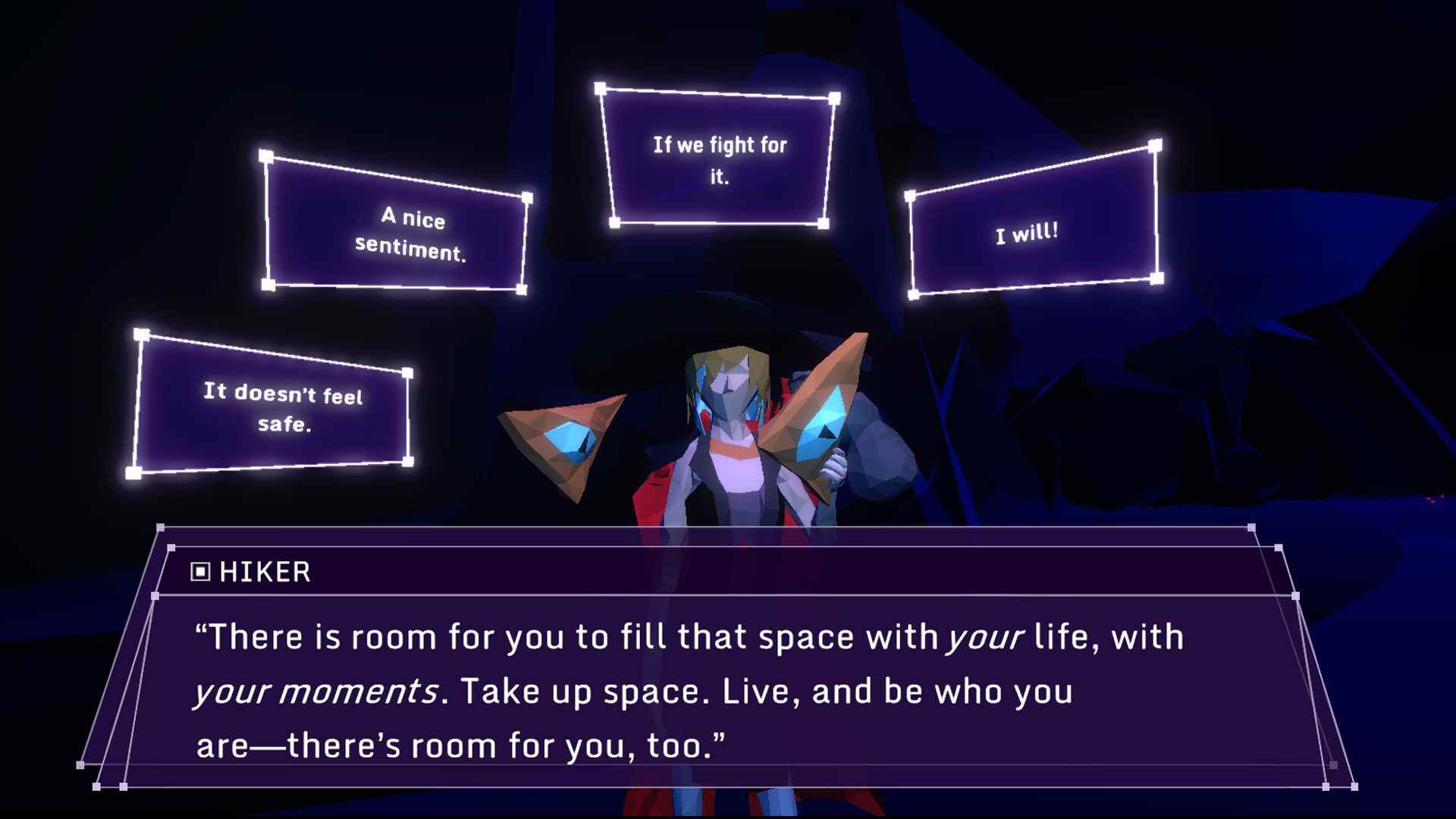

Claris Cyarron: Projection is such an important part of Glitchhikers. You have these conversations that are specific – each hiker has their own perspective, and some of them have an arc across the multiple times you meet them – but they’re not demigods. They are looking up at the same night sky in tiny awe at the size of it, and they have a certain perspective. Maybe they know more or less than you about certain things, but everyone is looking out and wondering.

There’s also the invitation to hear your own story in the words of the hiker while looking out of the window. Even in First Drive we have a character who mentions the word ‘sonder’, which is the idea that all the other people out there have lives as rich as you. You look out at the trees, and think “what’s that lake like? What’s it like to be there?” You have this invitation to not always project yourself into the car or into the train, but to project yourself further. That leap really brings people down the rabbit hole.

I think the other thing we wanted to do is help bring people back out of that rabbit hole. The play sessions themselves are fairly short, and you can string them together however you like. We have long play sessions too, and if you don’t want to be brought out of the experience for two hours go for it! We want to have a space for you, but we also want to get you back out into the world and remind you that as much magic as there is here, the source of that magic mostly is the real world. It’s us talking about real cool shit that’s out there, real difficult problems that have solutions that are waiting to be discovered. And that promise that there’s stuff out there to get.

From an aesthetic perspective, Glitchhikers does have this obvious glitchy quality to it as the name suggests, but it also taps into that retrowave aesthetic and almost has a vaporwave quality at times – particularly with the color palette. Why did you choose to make that decision? Was it partly the nostalgic pang that the style pulls in, or was there another reason behind that?

Claris Cyarron: The influence of our technical director ceMelusine (Phil Storey) cannot be understated. He brought us together with the idea of a game that would be about driving alone at night from Calgary to Vancouver. We then made it about driving alone in general, not about a particular journey or experience. He was very keen to do the 3D modelling, and he discovered the aesthetic that he liked.

When we wanted to push that forward we wanted to ask ourselves how much we wanted the CG/3D models versus the stylised thing that we ended up with. Our art isn’t really low poly–

Lucas J.W. Johnson: There are many polys!

Claris Cyarron: It twists and undulates, and folds in on itself almost like origami. We really wanted this sense of digital material, that’s both giving this kind of nostalgic wink – I know this is what you expect me to look like – but also making you think about the ways that this isn’t that. The way that digital material can have so many more undulations. Something that seems flat and blocky can be much more data intense than a standard model. We wanted the game to really wear its digital core on its sleeve in a lot of ways. We wanted that music component to also bring that in, with classic ‘80s glassy synth sounds as well as bringing in that vaporwave and synthwave vibe.

Lucas J.W. Johnson: As Claris implied, a major part of our starting point was that we wanted it to still feel like First Drive. It was limited by our capabilities – Phil did the 3D modelling and Phil’s not a 3D modeller, but he did a great job! – and First Drive was very much low poly. So we wanted to take that aesthetic, and make sure that people who played the original game maintained that sense of it still being Glitchhikers even as we pushed forward into The Spaces Between. We wanted to keep that aesthetic and then as Claris said push it forward.

Another big part of it too is the surreal. It’s a big part of Glitchhikers, especially the designs of our characters and even the designs of our conversations to keep them from being too real. There’s only one character in the game that could pass as human. Everyone else has something off about them in some way, or they’re utterly not human. When I’m writing the conversations, even as I’m writing about a very real, very specific issue that I want to talk about, I’m always thinking about how I pull this back into the weird. You can be deep into a conversation, the character says something, and you go “wait, what?! What did you say?”

The very first character in First Drive talks about what she did as a kid, and then ends the conversation with “too bad I was never really a kid.” And then disappears. We don’t want it to feel too realistic: we want to have that separation, have that element of the surreal and “did I just see what I think I saw?” that comes through in all of the journeys in different ways. All of this creates this bit of separation, this element of stepping out of the game, not getting sucked into it, and feeling too real about it. We’re talking about deep subjects in some of these conversations – really hard subjects – and so we wanted to make sure that it wasn’t too much of that.

It’s also the surreal of late night mind wandering. Travelling alone at night is a weird, surreal experience, and you think about weird things. It’s like being half asleep, and those weird dreams that you have are always a little bit off. All of those elements really come together to make that Glitchhikers experience.

Claris Cyarron: One last thing, and much more from a technical angle. Something that was both a factor for Phil when he was working on First Drive and all the way through to the development of The Spaces Between was having this low poly style that’s faceted to catch the light. We don’t do a lot of texture, so instead we made these surfaces be at different angles to catch lighting conditions, to catch shadow and to have detail that isn’t exactly always explicit. Again, players can project the meaning into it that they want.

You mentioned music during the last question. It’s been an integral part of many Silverstring Media projects over the years. Why do you think music is important – big question there! – and how did you decide to implement it here?

Lucas J.W. Johnson: A big part of it is our composer (Devin Vibert). We went to school together, and really wanted to bring his perspective into a lot of the projects that we do. For early projects we were able to add music into them because we had this relationship, and he was keen to help out. It really helped create some of our voice and some of our ideas for a lot of our projects.

When we did Glitchhikers – he was the composer for the original Glitchhikers and he’s the composer for The Spaces Between as well – it was so outside of his usual voice in music. He was doing a lot of orchestral stuff and then some rock, and then Glitchhikers is so different. It’s this glitchy, torn apart electronica, but he really knocked it out of the ballpark in First Drive. It was so impressive to see him shift gears so much and produce the music for First Drive, which was again one of the things that people really latched onto in the original game. The Spaces Between really expands on that; the soundtrack that is being released alongside the game is over four hours of music.

We’re all quite musical, or at least the three of us are – Claris, me, and Devin. I went to school with Devin, and we were in a band together. Claris is also into music and helped with some of the compositions in the game. So that’s always been something that has spoken to us. When I’m listening to music as I’m working, 50% of the time it’s video game soundtracks. That’s the kind of stuff that I go to and it does so much to add to the experience that you’re having. Music can manipulate emotions in such a visceral way.

It’s true in other projects too. I did a novella called Azrael’s Stop for Silverstring Media. It’s an ebook and a soundtrack. There’s no interactive experience but music as part of that was an integral piece, because again it’s always an important part of how I think about storytelling, creating those spaces and creating those emotions.

Claris Cyarron: I think the way that leitmotifs, soundtracks, and that kind of composition that Devin is so talented at is very similar to the ways in which Lucas and I approach narrative design. It’s about layering in meaning, having these threads that come up and connect to other things – whether intentionally or just laying them in together expecting that players can make that connection. If they have a set of particular experiences, any one of them could be a stand-in for what we are metaphorically talking about.

We had a really clear idea during First Drive for what we wanted the sound direction to be. It was so impressive because it was so outside of Devin’s wheelhouse. We were talking about late night radio, The Disintegration Loops, driving alone at 3AM in East Texas listening to NPR and stuff like that. But in the run up to us starting to work on The Spaces Between I was starting to get more into electronic music production and sound design.

Stepping into the role of Creative Director I was working with Devin quite closely throughout, working on some of the tracks directly with him and also just discussing the different styles we wanted to have for the modes. We wanted each journey type – including the convenience store, which acts as our menu mode – to have a different sonic palette. Whether it’s the kind of vaporwave jingle fodder in the convenience store, the more pop sensibilities that you have on your glitch pod in the walk, or the more folk sensibilities in the train where there’s a sense of physical instruments.

We also wanted to bring in the sense of the digital, proudly wearing on our sleeve where we are messing with your expectations. A lot of the time when you’re hearing an instrument sample and you think it’s definitely a real instrument, it wasn’t. We were very specifically looking for, and I challenged Devin to find, sound sources that were extremely difficult for both laypersons and experts to be able to say decisively “I know where that came from.” We wanted to blend that feeling of “is that weird synthy thing actually a bass clarinet and not a synth at all?” I don’t know – it could be! It was all about bringing in this notion of synth voices doing the things that they do so well, whether it’s something glassy or that fat analog Moog sound.

It was really fun to be able to speak Devin’s language so much more and talk about sound design. How to get specific timbres and tonalities out of parts of the music was a rewarding experience for me, and something that I think entirely separates First Drive from The Spaces Between. We weren’t just trying to capture one general style but a whole lot of different styles for different modes and different reasons. We wanted each mode to feel like a different sonic world instead of this tightly curated soundtrack. It feels like it’s somebody’s Glitchpod, or some busker who is playing the songs that they want to play, or some radio DJ who’s got a specific journey in mind. It’s the radio show that you could tune in day after day and not necessarily hear the same thing, as it’s going to be a little different each time.

Glitchhikers: The Spaces Between releases 31 March 2022 for PC and Switch.