Dusseldorf The founding story of Jerome Lange, Marco Trippler and Lasse Steffen shows how much potential can arise at universities: They quit their student jobs in order to set up the Koppla company in 2020 and develop software for large construction sites. But money was tight. “In the beginning I had less than 100 euros in my account,” says Lange.

The three of them have the University of Potsdam to thank for the fact that they made it. Katharina Hölzle, former professor at the Digital Engineering Faculty, motivated her not to give up. Hölzle helped the students with the applications for start-up grants, discussed the business model with them and networked them with experienced entrepreneurs.

“The university motivated us to keep going,” says Lange. And it was worth it: Koppla is now a start-up with 20 employees. The venture capitalists Earlybird and Coparion invested 1.6 million euros last year.

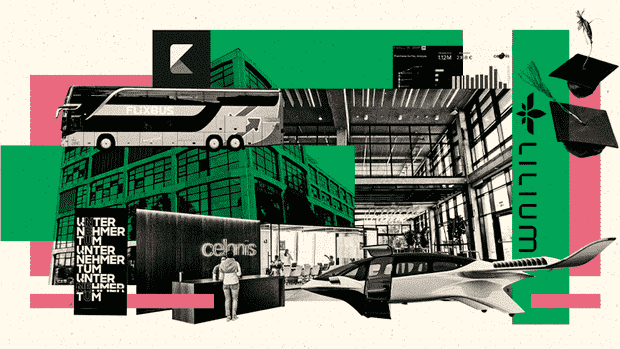

Many young German entrepreneurs tell such stories. The software company Celonis was founded by three students from the Technical University of Munich (TUM) and achieved a valuation of 11 billion dollars. The air taxi developer Lilium and the mobility provider Flix Mobility also originated at universities. “The innovation potential at German universities is immense,” says Nicola Breugst, TUMProfessor of Entrepreneurial Behavior. However, this is often not used in an international comparison.

Top jobs of the day

Find the best jobs now and

be notified by email.

Many ideas failed when they were created, says Breugst. The universities decide whether a start-up will be successful. There are “countless exciting research results waiting to be used commercially. But in the rarest of cases, it succeeds,” she says.

This has significant effects on the German economy a McKinsey analysis. Although Germany is strong in basic research, the results are rarely translated into concrete applications. The number of US technology companies with a turnover of more than one billion dollars exceeds that of German companies by a factor of 4.5.

Entrepreneurial activity in the early phase is more than twice as high. This refers to the share of the population of all 18 to 64-year-olds who are active as entrepreneurs or part of the management of a newly founded company.

Calculations by venture capitalist Earlybird come to similar conclusions. Every year between 45,000 and 60,000 new technologies are developed at European universities. After all, half of the ideas are used to set up a start-up. However, only half of these start-ups then seek financing. “75 percent of the innovation potential is lost,” judges Earlybird.

“Universities have to leave their ivory towers and commit to a living entrepreneurial spirit,” says TUM President Thomas Hofmann. The “entrepreneurial courage must be carried from the top of the university to all areas of the university”.

But how can this be achieved? Three factors in particular play a role in paving the way for start-ups from the lecture hall to the office.

1. Create a new mindset

TUM professor Breugst knows the problems that founders face. To date, she has accompanied more than a hundred start-ups. Her conclusion: Mental factors – the “mindset” – are given too little attention in the academic world. It’s not due to a lack of ideas, but “to the wrong incentive system of the universities,” she says.

Researchers were more focused on the next publication than developing a new business model. Those wanting to found a company have to bridge the gap between the meticulous way of thinking as a researcher and the pragmatic approach as an entrepreneur. “Perfectionism is not the ideal mindset for founding a company,” says Breugst.

The professor for Entrepreneurial Behavior at the Technical University of Munich sees great potential at German universities – which is rarely used.

(Photo: Technical University of Munich)

In her lectures, Professor Hölzle talked about how different thinking is at universities and in the private sector. She established a chair for IT entrepreneurship at the Digital Engineering Faculty of the University of Potsdam and the Hasso Plattner Institute (HPI). “I don’t have any strategies for teaching students how to get good grades,” says the 48-year-old.

Before her habilitation, Hölzle worked as an industrial engineer for the semiconductor manufacturer Infineon, then for a management consultancy and a US start-up. There she learned pragmatism and the ambition to meet customer needs. “Does my work create added value for the customer?” she often asked her students.

She also wants to teach them to work together in interdisciplinary teams. It is not the lonely scientist or the ingenious special team that is wanted, but diverse knowledge. The ability to develop business models is based on this. Founding only works in a team.

Breugst confirms this: Founders are dependent on the knowledge of various disciplines. People with a technical background focus on the product, while business graduates understand how markets work.

2. Universities share in the success

In the USA it is taken for granted that science and entrepreneurship merge. Faculties are often even part of the founding team. Stanford University, for example, has its own “faculty-associated start-ups” segment.

Isabel Schellinger experienced how this works. During a research stay at Stanford for several years, she researched the mechanisms involved in the development of abdominal aortic aneurysms. She and her team patented the results in the USA.

A US patent motivated Isabel Schellinger to found a company in Germany.

On the basis of the patent, the scientist founded Angiosolutions after her return to Germany. The company develops innovations such as implants for the treatment of vascular diseases. “If the university hadn’t made us aware that our research results have start-up potential, we probably would never have thought of starting our own company,” she says. “The patent was the impetus to develop a product from the research.”

Universities can also get involved in Germany, but it is complicated, says patent attorney Thomas Kitzhofer advises those interested in founding a company on corporate and patent law with the “UnternehmerTUM” initiative. Because then the law on employee inventions applies. The patent rights would lie here jointly with the university and the founders, so that they could stand in each other’s way.

If start-ups do not have the right to register, transfer and use patents, they are often unable to act and are unattractive for investors. According to Kitzhofer, however, negotiations between the university and the entrepreneurs are possible.

>> Be there: At the Handelsblatt Innovation Summit we show the latest ideas and products from the research laboratories and companies

From the perspective of the founders, the participation of the university can be very useful. They would benefit from the network and the experience of the professors, says Kitzhofer. For universities, participation is also financially lucrative and “an incentive to promote entrepreneurship”.

Universities are also learning to think entrepreneurially. Stanford, for example, has an internal technology transfer office that checks scientific work for patent opportunities before publication. “It was just a couple of emails,” says doctor Schellinger – “not a major bureaucratic act.” It deters scientists who often fail to recognize the potential of their own research. “We had a system that believed in us, otherwise I would have neither a patent nor my own company.”

There are also technology transfer offices at German universities. The University of Potsdam even opened a transfer professorship last year. “Germany is becoming more and more founder-friendly,” says Schellinger. For TUM President Hofmann, it is a “mutually reinforcing process”. “When universities have produced start-ups, they can also support new generations of founders,” he says.

After all, the new federal government wants to take on the topic with the “German Agency for Transfer and Innovation” (DATI). It is intended to ensure that innovations from universities and research organizations develop more quickly into new business ideas for start-ups. An external agency should therefore support innovative professors.

3. Access to investors and infrastructure

A lack of investment is also one of the reasons why Germany falls short of its potential when it comes to founding a company Thomas Prüver, partner of the auditing company EY. According to the Start-up Barometer 2022 received German start-ups received more than 17 billion euros in venture capital last year.

This means that the total volume has more than tripled, he says. But in Germany “still little is invested in relation to gross domestic product (GDP).” In terms of economic power, start-ups in Germany should have 100 billion euros at their disposal – more than five times as much as before.

Once the company has been founded, start-ups need access to investors and spatial infrastructure, such as offices or laboratories, in order to further develop the product, says TUM Professor Breugst. An example of this is the Artificial Intelligence Entrepreneurship Center (KIEZ), a model project of the Berlin universities financed by the Ministry of Economic Affairs. It supports science-related companies, especially promising AI companies.

The so-called accelerator offers start-ups infrastructure, such as office space, access to job portals and mentoring from AI experts. At the end of the six-month program there is a presentation to venture capitalists and industry representatives.

One of the startups is Levity. It helps companies automate routine tasks and evaluations, such as sorting customer service emails according to relevance. The program gives Levity access to experts, praises co-founder Gero Keil. They would have helped the young company with market research, for example. Through the program he was also able to recruit hard-to-find specialists.

Access to expert knowledge, skilled workers gained: The co-founder of the start-up Levity praises KIEZ, a model project founded by the Ministry of Economic Affairs and Berlin universities:

In Munich, UnternehmerTUM gives start-ups access to the market with their own venture capital fund. The early-stage investor specifically promotes technology-based companies and is financed by successful start-ups, among others. Celonis and Flixbus as well as TUM economics professor Ann-Kristin Achleitner are involved.

In Potsdam, it was Hölzle who introduced Koppla to investors. But sponsors also approached the founders on their own. Lange wants to use the investor money to further develop its software in order to speed up lengthy construction projects. Now the founder only has to find specialists who are familiar with software-as-a-service. He’s not worried. At university he learned to “deal with uncertainty”.

More: The new power of the founders: Why the start-up scene is changing massively