Berlin From a technical and economic point of view, hydrogen could also flow through the existing German natural gas network at the end of the fossil age – which, if produced in a climate-friendly manner, is regarded as the energy source of the future. This is shown by the calculations of a project by around 100 players from research and business on behalf of the Federal Ministry of Research. The paper is available to the Handelsblatt.

In the expansion stage, a hydrogen network with a total length of 10,000 kilometers could bring hydrogen to where it is needed, primarily through pipelines through which gas still flows today. “The first milestones of the ‘TransHyDE’ project confirm that the ramp-up of a hydrogen economy in Germany is possible and sensible from a technological and economic point of view,” said Federal Research Minister Bettina Stark-Watzinger to the Handelsblatt.

While the feared high costs would have made such a network appear unrealistic, it is now clear “that hydrogen can be transported inexpensively in pipelines up to a distance of 8,000 kilometers,” said the FDP politician.

Only then are other transport routes more efficient, especially when bound in ammonia. “Of course, we also have to develop this, but I’m still encouraged by the realization that we can develop the hydrogen network of the future from today’s gas network at low cost,” says Stark-Watzinger.

Top jobs of the day

Find the best jobs now and

be notified by email.

Therefore, it is now important to quickly set up a hydrogen infrastructure consisting of networks and storage facilities in order to “massively accelerate” the development of the hydrogen economy. Because only green, climate-friendly produced hydrogen offers the “great opportunity to combine energy security, climate neutrality and competitiveness”.

The experts from “TransHyDE” headed by coordinator Professor Mario Ragwitz from the Fraunhofer Institute for Energy Infrastructure and Geothermal Energy (IEG) have developed a model for a hydrogen network in 2030. A new construction of pipelines would be necessary “only to a small extent, since the vast majority of pipelines are part of today’s natural gas pipeline network,” they write.

This network could then be connected to that of other European countries and “in the expanded state, with a length of around 10,000 kilometers, cover most of the German hydrogen demand”.

The scientists are thus building on an idea that the operators of the gas grids first presented at the beginning of 2020: They want a Build a nearly 6,000-kilometer-long hydrogen transport network, more than 90 percent of which is based on the use of the existing natural gas network. It is intended to connect the future hydrogen production centers in northern Germany with the major customers in the west and south.

The concept of the Fraunhofer experts goes in a similar direction. They assume four scenarios: These range from the exclusive use of hydrogen in the steel and chemical industry as a basic model to widespread use in industry, transport and buildings.

This corresponds to a range of around 300 to 550 terawatt hours of hydrogen for the year 2045. By 2030, the steel industry will be the largest consumer at a few locations – the network for their systems could then be expanded bit by bit.

Test field in Emsland for hydrogen transport in old gas pipelines

On a test field in Lingen in Emsland, “TransHyDE” now wants to investigate what needs to be considered so that hydrogen can be transported safely in converted pipelines. From March 2023, the quantity and quality measurement of hydrogen is to be developed there “up to an official level” and thus provide the basis for a publicly accessible network.

A prerequisite for the use of today’s gas lines is that they are no longer required. The reallocation of the gas to hydrogen pipelines would ensure the survival of the gas network operators.

However, this is not without political controversy. The EU Commission is critical of the cross-financing of the hydrogen network expansion via the network fees of natural gas users. The Brussels officials have a strict separation of the two networks in mind. Ultimately, this would mean that the hydrogen lines would have to be completely rebuilt.

Other questions arise when importing hydrogen. Since most of the green hydrogen required in the future will have to come from countries where there is far more sun and wind available for its production than in Germany, solutions are needed for its transport and distribution beyond pipelines.

“TransHyDE” is primarily investigating ammonia as a carrier medium. As it is one of the world’s most produced chemicals, there are years of experience in transporting it here.

Ammonia is the chemical compound of nitrogen and hydrogen and can be used directly, for example in the chemical industry. However, it can also be split back into nitrogen and hydrogen after transport. The experts are now working on how hydrogen can be bound particularly efficiently in ammonia and how it can be released again.

Energy law must also be made “hydrogen-ready”.

Another goal is to make the energy law “hydrogen-ready”. There is still a need for improvement here, especially with the definition of green hydrogen. Inconsistent definitions are currently leading to legal uncertainties. At EU level, there is a particular debate as to whether green hydrogen is only considered sustainable if it is produced exclusively with electricity from new, purpose-built solar and wind power plants and only excess electricity is used for which it was available at the time of hydrogen production there is no other use.

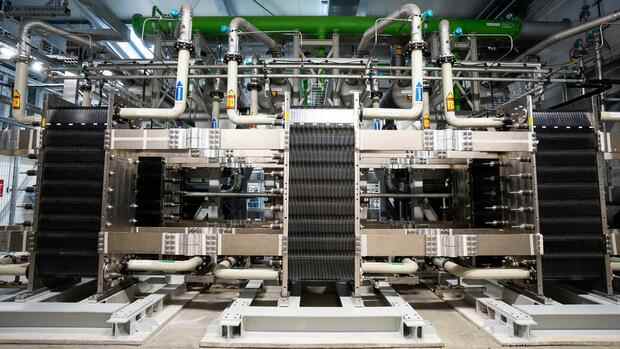

On the way to the hydrogen age, the Ministry of Research is funding two other projects in addition to “TransHyDE”: The “H2Giga” project is about the series production of large electrolysers, i.e. the systems that produce hydrogen and that Germany would like to sell worldwide.

“H2Mare” is about hydrogen production at sea. The ministry is providing around 700 million euros for the three projects up to 2025.

More: Germany’s 15-year gas deal with Qatar covers only a fraction of LNG needs