The industry is particularly suffering from production bottlenecks.

(Photo: dpa)

Frankfurt If inflation is a word that scares consumers and investors, then that applies all the more to the term stagflation. And this term is currently causing a sensation. The major US bank JP Morgan, for example, writes in a new study: “In recent weeks, possible ‘stagflation’ has been a prominent topic in discussions with our customers.”

What exactly does “stagflation” mean? That’s where the problem begins: There are two different definitions. One means by stagflation the coincidence of unemployment and inflation. According to the second, however, an essential element of the phenomenon is, as the term suggests, “stagnating”, ie only weakly growing, economy.

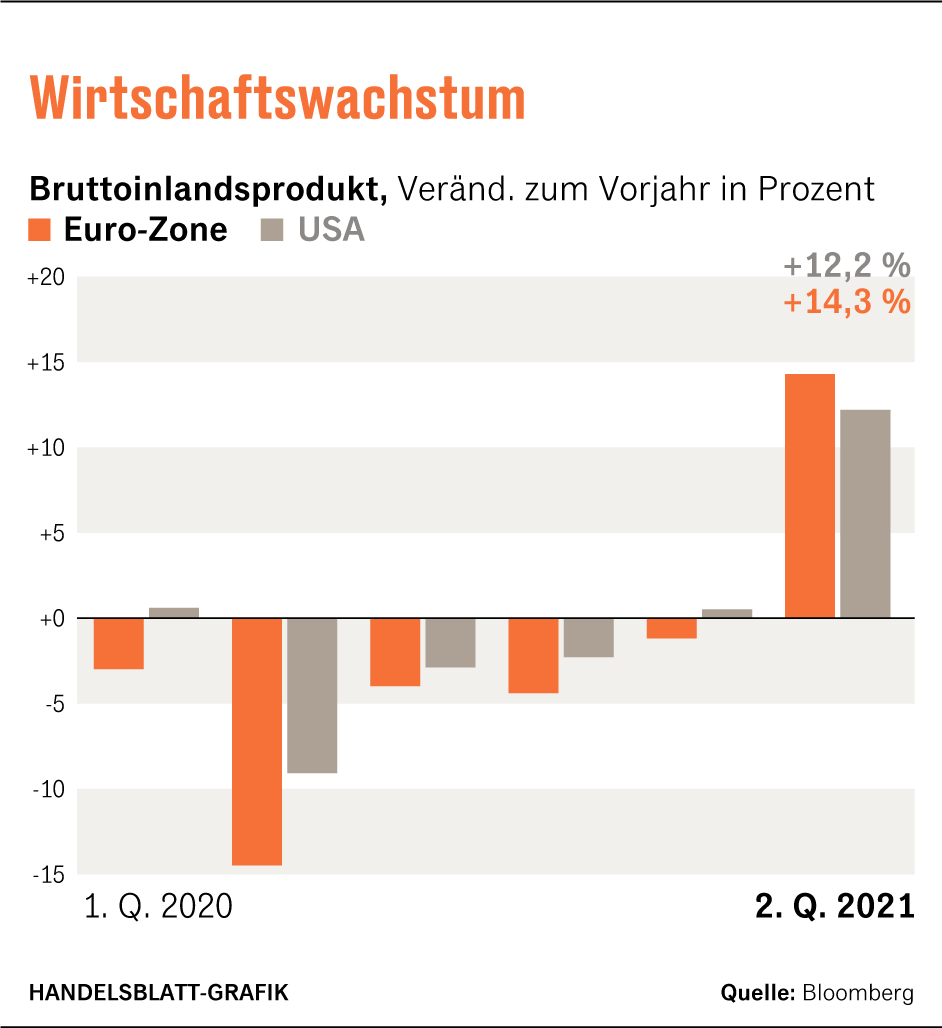

It is therefore controversial among investment strategists and economists whether we are in a phase of stagflation at all. JP Morgan, for example, sees “tentative approaches at best” because growth in the USA in particular is by no means weakening. Karen Dynan of the Peterson Institute in Washington argues in a very similar way: “If economic growth is above the long-term trend, it can hardly be called stagflation.”

In doing so, she contradicts prominent colleagues such as Larry Summers and Robert Rubin, who consider the term to be entirely appropriate with a view to relatively high inflation and a still weak labor market.

Top jobs of the day

Find the best jobs now and

be notified by email.

Compared to the 1970s, it lags

This is precisely why the topic is boiling: Because inflation is rising, but at the same time the labor market is still a long way from reaching full employment, and that applies to Europe as well as to the USA. It is reminiscent of the 1970s and it can confront the central banks with a bad decision: Either to fight inflation and risk even more unemployment – or to let it continue and risk losing control.

In both cases it can happen that in the end nothing is won and monetary policy is stuck in stagflation. But in the 1970s growth was weak in some areas, and at the same time there were strong unions who were able to convert high prices, such as oil, into high wages, creating an inflationary spiral.

Dynan therefore doesn’t think the Seventies are a good comparison. It trusts the central banks to intervene in good time before prices start to spiral upwards.

Comments from members of the ECB’s shadow council, a panel of monetary policy experts moderated by Handelsblatt, largely confirm Dynan’s point of view. Jörg Krämer, chief economist at Commerzbank, says about the situation in Germany: “With a view to the winter half-year, one can speak of stagflation.” He fears that the inflation rate in November could even have a five before the decimal point. At the same time, he predicts that the important German auto industry will “even stagnate” in the fourth quarter due to material shortages and falling demand from China.

This could “significantly dampen growth in the euro area”, especially since a new corona wave threatens. For the USA, however, Krämer also considers the term “stagflation” to be “less appropriate” because Commerzbank expects growth of three percent there in the fourth quarter of 2021.

The wage-price spiral is considered unlikely

Andrew Bosomworth from the bond specialist Pimco rates the risk of stagflation as “quite low”. He argues: “The workforce is no longer as strongly organized as it was in past decades.” Therefore, he does not fear a so-called second-round effect: This could occur if employers and trade unions react to the increased inflation and therefore agree higher wages. Such a wage-price spiral could develop a strong momentum of its own.

Frederik Ducrozet from Pictet expects inflation to remain at a higher level for a long time due to rising energy prices. But he, too, does not believe in second-round effects, especially with a view to Europe. Katharina Utermöhl from Allianz also expects subdued wage developments in the euro area, which can be attributed to the still ailing labor markets. She considers the bargaining power of the trade unions to be “severely limited” compared to the 1970s.

More: The central banks’ dilemma