Frankfurt, Brussels After the European Central Bank (ECB) Council meeting in early September, there was one big winner in the markets: the banks. The shares of Deutsche Bank, Commerzbank and other European institutions increased significantly. And this was not only due to the decision to raise interest rates.

Another point was almost more important: Contrary to what many experts had expected, the ECB refrained from restricting its TLTRO III loan program. Behind the abbreviation hides a highly lucrative business for many financial institutions. The interest that banks have to pay for these loans is well below the rate they collect when they park money overnight at the ECB. The sums at stake are enormous: the ECB has lent the banks a total of 2.1 trillion euros as part of the program.

The US bank Morgan Stanley is assuming extra profits of up to 24 billion euros, the rating agency Scope even comes to 40 billion euros when other factors are taken into account. Critics speak of a billion-dollar gift to the financial sector. “Now the least that the ECB can do is ensure that banks are not the winners of a crisis again,” says Michael Peters, an economist at the Finanzwende association, which is critical of banks.

Seven Green MEPs, including German party spokesman Rasmus Andresen, argue similarly. “It is unacceptable that the ECB is helping banks to make tax-financed profits while financing costs are increasing for all companies and households,” they write in a letter to ECB President Christine Lagarde, which is available to the Handelsblatt. That is why the Greens-EU parliamentarians are calling on the central bank to “stop the banks’ chance profits”.

Top jobs of the day

Find the best jobs now and

be notified by email.

The Economic Committee of the European Parliament also sees a need for action, according to the Committee’s annual report on the ECB. One regrets that the central bank has not yet addressed this issue.

More on the current monetary policy discussion:

ECB boss Lagarde has so far remained vague on the subject. At her press conference after the September council meeting, she said they would review the terms in due course. She signaled possible adjustments to the remuneration of banks’ reserves. In central bank circles it is expected that the ECB will make a decision before its next monetary policy meeting in October. However, this could be less extensive than the critics hope, because interventions are complicated.

The monetary policy situation has changed fundamentally

The current conditions of the program were decided during the 2020 pandemic. The ECB offered the banks money on extremely favorable terms. The institutes were able to borrow money from her in several tranches for three years. In June 2020 in particular, the institutes grabbed it and borrowed 1.3 trillion euros.

The interest rate was minus one percent in the first two years if the banks met certain criteria when granting loans. The institutes received a bonus of one percent from the ECB if they borrowed money from it. They could then invest the money that they did not use for lending back with the central bank and only had to pay the negative deposit rate of 0.5 percent for it.

At that time, at the beginning of the pandemic, the economy in the euro area had collapsed dramatically. The ECB feared that banks would hold back on lending, which would have exacerbated the crisis. In this situation, she wanted to take massive countermeasures and thus support the economy. When the ECB launched the TLTRO programs, inflation was below the 2% target. But then she shot up.

As a result, the situation is very different today. “The monetary policy situation has changed fundamentally compared to the time when the conditions for TLTRO III were set,” explains Jens Eisenschmidt, European economist at US investment bank Morgan Stanley. “Back then, the aim was to stimulate the economy as much as possible. At the moment, on the other hand, given the high inflation, there is no longer any reason for additional stimulus.”

Bank representatives demand reliability

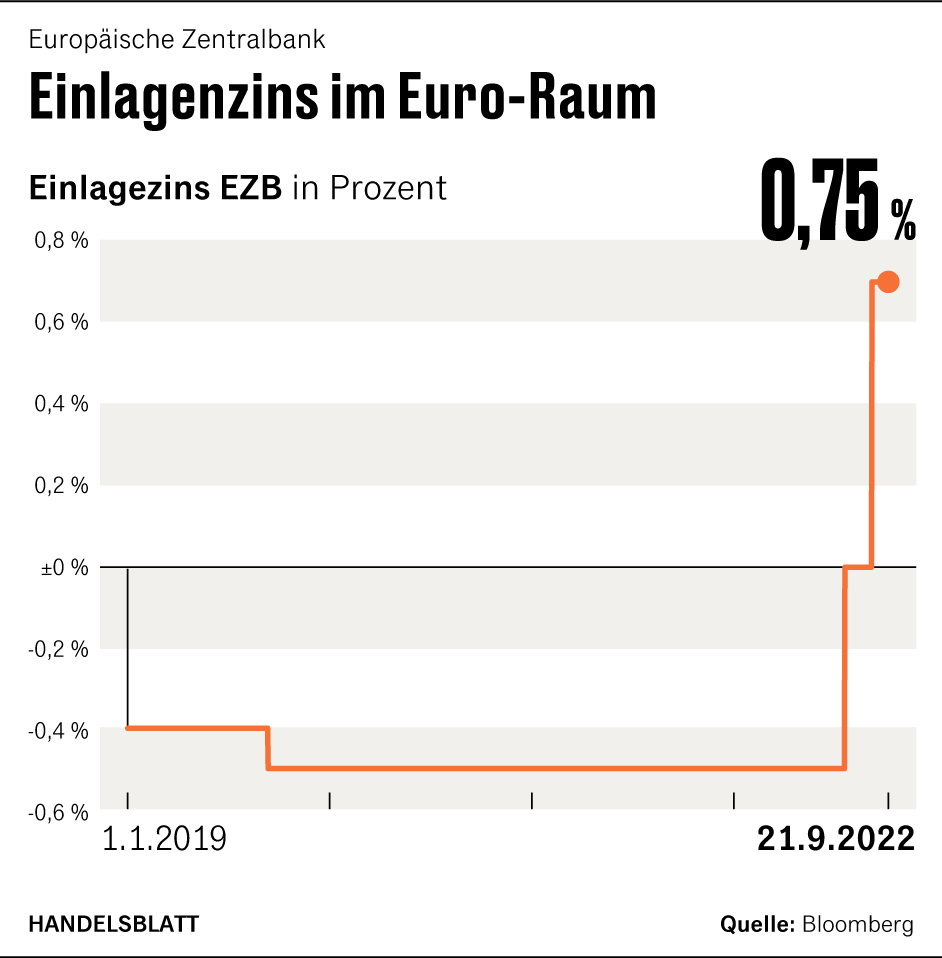

The ECB had to reverse monetary policy and raise interest rates, making the TLTRO programs much more attractive to banks than originally planned. Instead of minus 0.5 percent, the deposit rate has been plus 0.75 percent since this month. This is a problem for the central bank, because it has set the conditions in advance for three years.

In the third year, the interest on the TLTRO is no longer minus one percent. It corresponds to the average deposit rate over the entire period, which means that it will probably remain in negative territory. The banks can therefore invest this money with the ECB and thus make a significant profit.

“The original assumption was probably that the deposit rate would remain stable for the full three years that TLTRO III runs. In this case, many banks would have repaid their funds from the TLTRO early in the summer of 2022 because it would no longer have been so attractive,” says Morgan Stanley economist Eisenschmidt. “However, the situation has changed completely as a result of the interest rate hikes by the ECB.”

In theory, banks can repay their TLTRO tranches once a quarter. In view of the turnaround in interest rates, however, the repayments have now turned out to be significantly lower than expected when the program was launched.

>> Read here: Higher margins, more collateral: Banks take a closer look at loans

Bank representatives argue that the institutes have relied on the stipulated conditions and granted loans based on them. They would find it unfair to change the TLTRO conditions retrospectively, after all they cannot retrospectively adjust the conditions of the loans granted at the time.

From the banks’ point of view, such a step would also damage the ECB’s credibility. The institutes could then not be sure in future programs of the ECB that the conditions set will remain valid.

All of this shows that when the ECB wants to limit bank profits, things get complicated. The ECB has various options, but all are fraught with problems. An overview:

1. Change in TLTRO Terms

One possibility would be that the ECB adjusts the conditions for the remaining term of the TLTROs until 2023 and demands a higher interest rate from the banks for this period, for example in the amount of the current deposit rate. This would squeeze banks’ profits and make exposure less attractive. This could prompt institutions to repay them earlier, which would reduce excess liquidity. This would currently be desirable from a monetary policy perspective.

“In principle, an adjustment of the TLTRO conditions would be the best solution, because that would start at the source of the problem,” says Eisenschmidt. “However, one does not seem to want to go this route, among other things because there could be legal problems.”

Because of the legal concerns, it is therefore likely that the ECB will take a different approach: previous statements by the central bank suggest that it is more likely to make changes to the remuneration of banks’ reserves.

2. Adjust reserve requirements

One possibility for this would be changes in the minimum reserves and their interest rates. Banks in the euro area are obliged to hold a certain amount of funds with the central bank. Currently, this reserve requirement is 1 percent of a bank’s certain liabilities, primarily customer deposits. The ECB pays interest on this minimum reserve requirement at the base rate of 1.25 percent.

In order to dampen banks’ interest income and reduce excess liquidity, the ECB could increase the reserve requirement and lower interest rates, for example to zero percent. The advantage of this variant would be that the ECB could skim off part of the banks’ profits and excess liquidity could be reduced.

However, this would not be very accurate and would act like a tax on the entire banking sector. This would also penalize institutions that have not used the TLTRO and have no way of reducing their burdens by prepaying their tranches.

3. Introduction of a reverse graduated interest rate (reverse tiering)

Another approach would be a so-called reverse tiering. When the interest rate on deposits in the euro area was below zero, banks were subject to allowances up to which they could deposit at least zero percent of their funds with the central bank, the so-called tiering. This system has become obsolete since the ECB raised the deposit rate to zero percent in July. It has been at 0.75 percent since the beginning of September.

>> Read here: The week of the big jumps in interest rates

However, an opposite variant would be conceivable. The ECB could pay banks that have used the TLTRO an interest rate below the deposit rate for deposits above a certain limit. The aim would be to get banks to repay part of their TLTRO loans. According to Morgan Stanley, that rate could be zero percent or slightly more. A variant would also be conceivable in which TLTRO volumes would be excluded from the positive interest rate.

The benefit of such a system would be that it would be more targeted than reserve requirement changes because it would target the banks benefiting from the TLTRO directly. In addition, banks would be given an incentive to repay part of their TLTRO tranches.

A disadvantage would be that such regulations are very complicated and may be difficult to implement in practice. They could also have undesirable monetary policy effects. In principle, the ECB wants to raise interest rates in order to combat inflation. However, if the higher interest rates are not applied to all deposits, the impact of higher interest rates might be reduced.

More: ECB fights inflation with historic rate hike